Liepos mėnesį žydų kultūros istorikas, jidiš literatūros tyrinėtojas iš JAV Davidas G. Roskiesas skaitė paskaitą apie aistringuosius ir poetiškuosius litvakus. Su džiaugsmu pristatome ilgai lauktą paskaitos vertimą į lietuvių kalbą.

Tekstas anglų kalba pateikiamas po lietuviškojo.

Įsimylėję litvakai

Davidas G. Roskiesas

Tiškevičių rūmai Trakų ir Pylimo (kuri anksčiau vadinosi Zavalna) gatvių sankryžoje yra tikras architektūros paminklas, ypač jų fasadas. Balkoną laiko du neoklasikinio stiliaus pusnuogiai atlantai, kurie mums primena apie XVIII amžiuje čia gyvenusius ir valdžiusius lenkų aristokratus. Jie susieja Vilnių su visai Europai anuomet būdingu judėjimu architektūroje, kuris sėmėsi įkvėpimo iš Senovės Graikijos.

Tiškevičių rūmai nuo tada daugsyk keitė savininkus. Kai 1971-aisiais pirmąkart lankiausi Vilniuje, čia buvo įsikūrusi sovietinė policijos akademija. Nebuvo nė minties užsukti vidun. Mano gidas Zalmanas Gurdus kalbėjo: „Ale yidn hot men oysgeharfet, ober di tsvey bulvanes shteyen nokh“ (visi žydai išžudyti, o šie du balvonai tebestovi). Šitaip Vilniaus žydai juokais vadino šį vietinį architektūros paminklą.

Kai 2000-aisiais lankiausi Vilniuje antrąsyk, sovietų čia jau nebebuvo. Paradinės pastato durys buvo atviros, o toje pačioje senoje būdelėje tebestovintis durininkas mus mielai įleido. Rūmus neseniai buvo perėmęs Vilniaus universitetas, bet renovacijos dar nebuvo pradėtos, todėl pastatas atrodė labai apleistas. Šalia jo nebeaugo liepos – per karą jas nukirto ir suvartojo kurui. Aš ilgai sėdėjau vidiniame kieme, pasakodamas savo žmonai Šanai, mudviejų draugams Monikai ir Stašekui iš Varšuvos bei vietiniam mūsų gidui Iljai viską, ką žinojau apie žydus, kurie čia gyveno tuo pat metu, kaip mano motina: 1906-1930 metais. Tuomet čia buvo ir Kochanovskio vaikų darželis, Macų spaustuvė, žydų našlaičių namai, Badaneso kepykla ir dar daug visko.

Vakar aš ten sugrįžau ir buvau nustebintas, ką toje vietoje pastatė universitetas. Nors dar ir nepabaigtas, tai puikus miesto atsinaujinimo pavyzdys. Bet praėjus pro automatines duris ir lipant viršun atvirais plieniniais laiptais, mano mintys klaidžiojo kitur. Man ši vieta gyvuoja ne istorijoje, ne architektūroje ir ne miesto renovacijose. Ji esti tik atmintyje. Čia ji atsiduria kitoje aplinkoje ir kitoje laiko zonoje. Atmintyje abu balvonai žymi įėjimą į Jidišland, vietą, kur litvakai buvo labai įsimylėję.

Taigi kviečiu jus į žydišką ekskursiją po mano mėgstamiausias atminties vietas.

Į šią ekskursiją jus kviečiu kaip kultūros istorikas. Juo tapau dėl dviejų priežasčių:

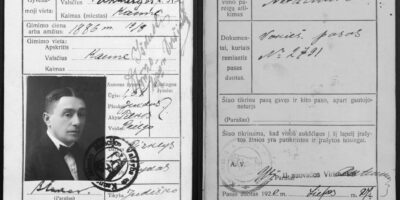

Pirmoji susijusi su tuo, kad esu litvakas. Buvimas litvaku yra mano žydiškosios tapatybės esmė. Tiek man, tiek kitiems litvakams Lita yra tarsi atskira, nepriklausoma geografinė-kultūrinė esybė. Tai LS (Litvakų sąjunga) ES viduje! Būti litvaku reiškia visam gyvenimui gauti pasą, kurį priima visur: Pietų Amerikoje, Australijoje, Kanadoje, Crown Heights rajone Niujorke, Sankt Peterburge ir Tel Avive. Tai unikalus būdas būti žydu: ir privilegija, ir visas rinkinys lūkesčių. Litvakas visiems yra rakštis panagėje. Ne be reikalo įdarytą žuvį litvakai gamina su pipirais, o ne su cukrumi.

Antra, aš esu feministas. Mano giminę sudaro ištisos kartos matriarchių. Iš Lietuvos kilusių žydų šeimų pavardės dažnai susijusios su matriarchalinėmis figūromis: Syrkis, Syrkinas (iš Sorkė-Sara), Rivkinas (iš Rivkė-Rebeka), Brochesas (iš Bracha), Reinesas (iš Rainė). Lygiai taip pat ir Roskesas kilo iš kažkokios pro-pro-prosenelės vardu Roiz, Rožė. Jos vaikai vadinti Roizkes kinder. Žodis Roizkes tapo Roskes, tada Roskies.

Mano gimtoji kalba yra jidiš. Nors mano tėvai kalbėjo dar keturiomis kitomis kalbomis, jidiš kalbą pradėta vartoti namie, kai mano tėvai pabėgo iš Europos ir atvyko į saugų prieglobstį Kanadoje, Montrealyje. Prie savo mamos aš buvau labai prisirišęs. Iš dalies dėl jos ir paskyriau savo gyvenimą jidiš kalbai.

Vilniuje gimusi mano mama ir Balstogėje gimęs tėtis kalbėjo litviš, t.y. lietuviškąja jidiš, vienu iš trijų pagrindinių jidiš dialektų.

Galų gale, aš ir susituokiau su litvake.

Pasinaudojant kultūros istoriko įrankiais, semiantis iš savo litvakiškos tapatybės ir iš feminizmo kaip žinių šaltinio, man pavyko perprasti kolektyvinės žydiškosios atminties DNR. Žinau, kas tai, ir žinau, kaip tai veikia.

Žydiškoji kolektyvinė atmintis išdėstyta aplink šventuosius, šventyklas ir šventą laiką. Šitaip kiekviena žydų karta kūrėsi pavyzdinį gyvenimą, pavyzdinę bendruomenę ir pavyzdinį laiką. Tam, kad iškoduotum kolektyvinės žydų atminties DNR, nebūtina būti litvaku, bet tai gelbsti, kadangi būtent Lietuvoje ši trejopa ašis, trišakis modelis pasirodė visu ryškumu. Šis modelis buvo toks tvirtas, kad išliko net pasauliui ėmus keistis.

Lietuvoje ryškūs pokyčiai pradėjo vykti drauge su naujos religinio atsinaujinimo srovės – chasidizmo – iškilimu XVIII amžiaus pabaigoje. Kol chasidizmas apsiribojo Podolės ir Voluinės miestais, kurie buvo į pietus nuo „įdarytos žuvies riboženklio“[1] ir kur gyventojai kalbėjo kitu jidiš dialektu, nebuvo ko nerimauti. Bet pradėjo sklisti kalbos apie naują kultūros herojų, vardu Izraelis Baalšemas. Jis mokėjo gydyti rankomis ir buvo cadikas, kitaip – šventasis, kuris darė daug litvakams neįprastų dalykų: sėkmingai pamokslaudamas ir mokydamas užsitraukė garsių Toros žinovų, tradicinės žydų bendruomenės elito, nemalonę. Dar blogiau – jis išpopuliarino kabalą, teigė karts nuo karto apsilankantis danguje ir skatino bet kuriuo metu praktikuoti mistinę maldą su keistomis ir ekstatiškomis dainomis ir šokiais. Staiga, nespėjus nė apsidairyti, chasidų maldos namai ėmė atsidarinėti ir Lietuvoje. Taigi rabinams atėjo metas imtis kažkokių veiksmų.

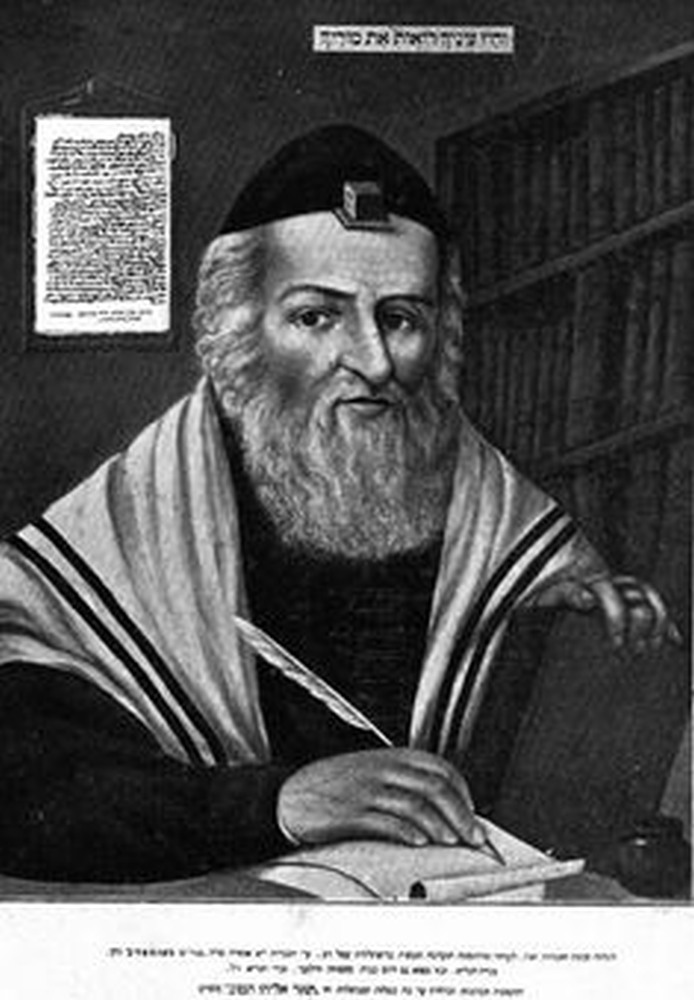

Šiam naujam dvasinio judėjimo modeliui galėjo pasipriešinti tik vienas žmogus – Elijas ben Saliamonas Zalmanas, kurio garbei buvo atkurtas Gaono titulas, iki tol nenaudotas keturis šimtus metų. Baalšemui tapus chasidizmo įkūrėju, Vilniaus Gaonas įkūrė „oponentų“ (hebr. mitnagdim) judėjimą. Tačiau, nors chasidizmo pradžią gaubia legendos, visiškai tiksliai žinoma, kada ir kaip prasidėjo mitnagedų judėjimas. Tai įvyko 1772 m., kai Elijas viso labo antrąsyk apsilankė shtotshul, Vilniaus Didžiojoje sinagogoje. Ten jis garsiai perskaitė nuosprendį, ekskomunikuojantį chasidus (o per pirmąjį savo apsilankymą Didžiojoje sinagogoje jis, būdamas viso labo šešerių su puse metų, aiškino Talmudą).

Kolektyvinėje žydų atmintyje ekskomunikavimo nuosprendžio – cheremo – tekstas svarba neprilygsta Martyno Liuterio „Devyniasdešimt penkioms tezėms“. Dauguma žmonių, kaip ir aš pats, jo net nėra skaitę. Vilniaus Gaono atminimas pagerbiamas kitais būdais. Jo įtaka siekė toli ir sklido plačiai per dvi nešiojamas atminties vietas: vieną elitinę, ir vieną populiarią. Elitiniuose sluoksniuose joks Babilono Talmudo leidimas neapsieidavo be Hagahot HaGra, jo rašytinių komentarų ir taisymų, atsiradusių puslapio paraštėse, ypač nuo tada, kai Vilniaus Babilono Talmudas, leistas našlės Rom ir jos sūnų spaustuvėje, tapo standartine Babilono Talmudo versija. Šitaip Vilniaus Gaonas patapo anapus laiko egzistuojančia tekstine figūra. Gaono šlovė buvo įkūnyta ir populiarioje meno šakoje, kuri jam pačiam tikrai nebūtų patikusi: jo portretas puošė visos Rytų Europos – ir ne tik – žydų namų sienas. Google paieškos sistema leidžia pasirinkti iš dviejų Vilniaus gaono atvaizdų: viename jis dėvi talitą (pamaldų apsiaustą) ir tefilin (mažą kvadratinę odinę dėžutę, kurion įdėtas maldos tekstas) ant galvos; kitame – prabangią šventiko skrybėlę.

Bet mums dabar svarbiausia tai, kokios istorijos apie jį keliavo iš lūpų į lūpas. Sykį prie jo priėjo sinagogos lankytojas ir paklausė: „Sakykite, rabi, kaip tampama Vilniaus Gaonu?“ Gaonas atsakė: „Vil-nor, vestu vern a goen, jei labai norėsi, tu irgi gali būti Gaonas“. Nelauk stebuklo. Nesitikėk, kad už tave darbą atliks cadikas. Dirbk, kad pats realizuotum savo siekius. Tai yra mitnagediškos-litvakiškos Toros esmė: Vil-nor.

Tačiau pavyzdinio asmens paieškos čia nesibaigė. Šalia mitnagedų ir chasidų, besigrūmusių daugiau nei šimtmetį, pradėjo reikštis nauja grupė, kuri vadinosi maskiliai, švietėjai, tseylem-kep. Tseylem-kop yra žmogus, kuris, įtariama, galvoje slepia krucifiksą. Jis tiek protingas, kad jam pačiam nuo to blogai. Jis pasiryžęs paaukoti pamaldumą dėl laisvos minties. Lietuva sparčiai patapo Haskalos, žydų švietėjų judėjimo, centru.

Skirtingai nuo cadiko ar rabino mitnagedo, kurie buvo kolektyvą atstovaujantys, į bendruomenės gyvenimą pasinėrę lyderiai, maskilis buvo vienišius, atstumtasis, eretikas. Dar blogiau: savo maištą maskilis pavertė autobiografijos tema – naujo žanro, kurį išrado Žanas Žakas Ruso. Pirmiausia Ruso modelį perėmė – ką jūs manote? – litvakai. Iš Žukovo Boroko miestelio netoli Myriaus miesto Didžiojoje Lietuvos kunigaikštystėje, kilęs Saliamonas ben Jozuė vėliau pasikeitė vardą ir, būdamas 38 metų Saliamono Maimono vardu išleido knygą Lebensgeschichte, parašytą laužyta vokiečių kalba. Taip pat autobiografijos ėmėsi Salantuose (netoli Kauno) gimęs ir hebrajiškai rašęs Mordechajus Aaronas Ginzburgas. Ar jie būtų likę Lietuvoje, ar išvykę į Apšvietos centrą – Vokietiją, autobiografijas rašę litvakai turėjo vieną bendrą bruožą: juos dar labai jaunus sutuokė su nemylimomis merginomis, ir todėl jie visą gyvenimą buvo nelaimingi.

Taigi pavyzdinį asmenį dabar įkūnijo trys besivaržantys ir be galo skirtingi žmonių tipai. Tačiau visi žydai sutarė, kad pavyzdinė vieta yra Jeruzalė, kurioje stovėjo pirmoji ir antroji šventyklos. Iš to sekė, kad kolektyvinėje žydų atmintyje Jeruzalė tapo kehila kedoša, Sandoros bendruomene. Kad žydų bendruomenė pasiskelbtų esanti ir va’em beYisrael, žydų tautos metropolija, ji turėjo tai pagrįsti senovine kilme. Pavyzdinė vieta buvo pripildyta Dievo buvimo.

Vilniaus pretenzija būti Lietuvos Jeruzale rėmėsi Didžiąja sinagoga. Kaip ir Jeruzalės šventyklos, Vilniaus shtotshul didybę galima buvo pamatyti tik iš vidaus, kadangi trečdalis pastato buvo įleista į žemę. Joje galėjo susėsti 3000 žmonių.

Panašiai kaip Jeruzalės šventyklos, Didžiosios sinagogos dauguma lobių buvo išgrobstyta, vėl ir vėl. Nuo pirmojo jos pastatymo XVI amžiuje, šią sinagogą tris kartus užpuolė ir sudegino Jėzuitų akademijos studentai ir jų bendrai. Paskutinį sykį ji buvo atstatyta po paskutiniojo 1635 m. pogromo. Panašiai kaip Šventyklą, sinagogą galiausiai sunaikino baisiausi pasaulio tironai. Hitleris ją apgriovė 1943 metais, o jo darbą pabaigė Stalinas. Kaip ir Šventykla, sinagoga buvo stebuklų vieta.

Trečią ir paskutinįjį kartą Vilniaus gaonas apsilankė shtotshul 1794-aisiais, kai rusų armija iš patrankų apšaudė tuo metu Lenkijai priklausiusį Vilnių. Shtotshul buvo pastatyta taip, kad galėtų atlaikyti ataką, taigi 72 metų Gaonas liepė visiems žydams joje pasislėpti. Tada jis atvėrė aron kodešą, šventąją spintą, kur laikomi Toros ritiniai, ir septynis kartus perskaitė 20-ąją psalmę iš Psalmyno.

Chorvedžiui.

Dovydo psalmė.

Teišklauso tave VIEŠPATS negandos dieną,

Jokūbo Dievo vardas tesaugo tave!

Tesiunčia tau pagalbą iš šventovės,

iš Ziono tepalaiko tave!

Teatsimena visas tavo atnašas,

ir tavo deginamosios aukos jam tepatinka!

(Vert. Antanas Rubšys)

Tada visi susirinkę žydai – vyrai, moterys, vaikai – patys septynis kartus pakartojo psalmę. Tą akimirką patrankos sviedinys pataikė į stogą, bet, užuot susprogęs, jis taip ir liko ten įstrigęs. Persigandusius žydus nuramino Gaonas: „Botl, botl di gzeyre. Blogio įsakas panaikintas“. Gaonui bekalbant lenkų karininkai nusprendė verčiau įsileisti į miestą rusus, negu leisti viską jame sunaikinti. Nuo tada kiekvienais metais tą dieną buvo kalbama padėkos malda, o bendruomenė surinkdavo ypatingą auką padėkoti už išgelbėjimą nuo mirties.

Jei esate litvakas, šis stebuklas jums turėtų itin patikti, nes jį paaiškinti galima dviem būdais. Akivaizdus paaiškinimas – Vilniaus Gaono maldos išgelbėjo Didžiąją sinagogą nuo sunaikinimo. Vien šio dvasios galiūno kalbamos maldos galėjo sulaikyti patrankos sviedinį nesprogus. Mažiau akivaizdus paaiškinimas – apdairus laikinųjų miesto šeimininkų lenkų sprendimas atverti Vilniaus vartus.

1800-aisiais, praėjus penkeriems metams nuo Gaono mirties, jo namų vietoje kahalas (žydų bendruomenės savivalda) pastatė kloizą – mokslo ir maldos namus. Kokia atminties vieta buvo kloizas? Jis įkūnijo paties Gaono pamaldumą ir neapsakomą asketiškumą. Kaip niekur kitur, Vilniuje pavyzdinis žmogus ir pavyzdinė vieta susiliejo į viena.

1902-aisiais taisyti ir originale netoliese pradėjo veikti Strašuno biblioteka, talpinusi tūkstančius hebrajiškų tekstų ir rankraščių, tarp jų – religinės ir grožinės literatūros, poezijos, mokslinių darbų, žydų ir karaimų istorijos traktatų, kelionių aprašymų ir chasidų tekstų, kuriuos visus surinko garsus Vilniaus maskilis Matas Strašunas. Taigi pavyzdinė litvakiška vieta apjungė apšvietą ir tradicinį pamaldumą, pasaulietines žinias ir Toros mokslus. Litvakai daug keliavo. Kad ir kur būtų, jie su savimi pasiimdavo dalį savo šalies. Amerikoje kita pasišventusių litvakų grupelė – Bernardas Revelis, Samuelis Belkinas ir Jozefas Soloveičikas – sukūrė Tora uMada (Tora ir mokslas) sistemą, norėdami Naujajame pasaulyje visam laikui įtvirtinti šį modelį. Tai – dabartinis Universitetas-Ješiva (Yeshiva University). Tuo metu, pradedant 1834-aisiais, Vilniuje susibūrė grupelė apie reformas galvojančių jaunų maskilių ir įkūrė Tohoras Hakoideš, pirmą žydų maldos grupelę Rytų Europoje, kurios etiketas griežtai reikalavo: Nekalbėti pamaldų metu! Tipiški litvakai.

O kaipgi pavyzdinis laikas? Jei būtumėte chasidas, pavyzdinis laikas jums būtų tuomet, kai cadikas dar buvo gyvas ir žydų tautoje tebevyko stebuklai. Jei būtumėte mitnagedu, žinotumėte, kad tik didis vedlys – rabinas – gali apsaugoti žydų bendruomenę nuo sunaikinimo. Didžiosios sinagogos buvo pasigailėta todėl, kad pamaldžioji bendruomenė laikėsi sandoros su Dievu. O maskiliai tikėjo emancipacija, todėl jų laiko suvokimas buvo linijinis, judantis į priekį. Šiandiena geresnė negu vakar, o rytoj bus dar geriau.

Kaip jau minėjau, nebūtina būti litvaku, kad iššifruotum kolektyvinės žydų atminties DNR, bet tai padeda – kadangi Lietuvoje vyko ideologinės kovos, kuriose grūmėsi ir aiškiau negu kur kitur matėsi skirtingi pavyzdinio asmens, pavyzdinės bendruomenės ir pavyzdinio laiko modeliai. Tačiau kol kas mes žvelgėme per labiau patriarchalinės bendruomenės akinius. Su rabinais, cadikais ir maskiliais yra viena bėda – jie visi paprastai būna vyrai. Tas pats galioja ir sinagogoms, bibliotekoms ir ješivos universitetams, kur ir vėl dominuoja vyrai. Kas būtų, jei į žydų ir litvakų kultūrą pažvelgtume feministiniu žvilgsniu? Feminizmas siekia lygybės ir prasideda nuo klausimo: kas buvo išstumta? Atsakymas akivaizdus: be moterų, vaikų ir jaunimo negali būti jokios kolektyvinės tapatybės. Atmintis prasideda namie ir mokykloje, šeimos susibūrimuose ir jaunimo grupelėse.

***

Karas jau buvo įpusėjęs. Mano tėvai, Maša ir Leibas Roskesai, kuriems 1940-aisiais pavyko pabėgti iš Europos su mano broliuku Benu ir sesute Ruta, dalyvavo vestuvėse Westmounto sinagogoje – prašmatnioje ir madingoje Montrealio dalyje, kur tuomet gyveno.

Nuotakai einant prie altoriaus, muzikantai užgrojo Mendelsono „Dainą be žodžių“. Tai sukrėtė mano mamą. Kaip jie galėjo pasirinkti būtent šią melodiją?

1919-ųjų balandžio mėnesio pogromo metu lenkų legionieriai ištempė dramaturgą A. Vaiterį į gatvę ir čia pat jį nušovė, kiaurai peršaudami ir jo merginą, kuri bandė jį apsaugoti savo kūnu – nuo tada ši melodija tapo šventu himnu. Jai žodžius sukūrė jidiš kalba rašęs poetas Avromas Reizenas, o per jų laidotuves visas Vilniaus jaunimas ir bendruomenės vedliai praeidami pro jų neštuvus dainavo:

Gražiausios dainos,

Melodijos gražiausios,

Nedainuoki jų, kai šypsosi sėkmė,

Dainuoki nuopolio metu.

Skambėkite, garsai nuostabūs,

Nors gegužė jau praėjo,

Nors jau saulės nebėra,

Nors ir miręs jau poetas.

,די שענסטע לידגעזאַנגען

,די שענסטע מעלאָדי

,ניט זינג בײַם בליִען

.נאָר זינג בײַם אונטערגאַנג

,קלינגט זשע הויך, איר שיינע קלאַנגען

,כאָטש דער מײַ איז שוין פֿאַרבײַ

,כאָטש די זון איז שוין פֿאַרגאַנגען

.כאָטש דער דיכטער איז שוין טויט

Tuomet mano mamai buvo 13 metų – tai laikas, kai žmogus yra labai paveikus. Ir nors jos namuose buvo kalbama ne jidiš kalba, o rusiškai, Maša įsiminė šios dainos žodžius. Daina jai įgijo tokią grėsmingą svarbą dar ir todėl, kad viena iš jos įseserių buvo gera Vaiterio merginos draugė – tos, kuri mėgino apsaugoti jį savo pačios kūnu. Taip pasielgi tada, kai kažką labai myli – vėliau mama paaiškino savo mizinik, jauniausiam sūnui. Pasiaukoji dėl to žmogaus.

Įžeista, kad šį šventą himną turtingi Westmounto žydai naudojo taip kasdieniškai ir tarsi lengvabūdiškai, tuo pat metu siaučiant milijonus mūsiškių sunaikinusiam karui, mano mama priėmė reikšmingą sprendimą. Ji nusprendė išsikraustyti iš tos miesto dalies ir su šeima įsikurti ten, kur kalbama jidiš. Po to sekė kiti sprendimai: leisti mano brolį į folksšule, mokyklą, kur vartojamos jidiš ir hebrajų kalbos, ir paskirti likusį savo gyvenimą (kartu su papildomomis mano tėčio pajamomis) jidiš kalba rašiusių poetų ir menininkų rėmimui.

Mano mamos istorijoje ir dainoje slypi trys svarbios pamokos apie tai, ką reiškia būti litvaku.

- Atmintis yra agresyvus veiksmas. Tai niekaip nesusiję su nostalgija, kurios paskirtis yra apmalšinti skausmą, susitaikyti su netektimi įsivaizduojant praeitį labiau derančią su dabartimi. Nors Reizeno sukurtame dainos tekste neminimi istoriniai įvykiai, daina sukelia jausmą apie Vaiterio kūrybingumo beprasmišką netektį. Po to išėjo ir Vayter-bukh, knyga Vaiterio atminimui pagerbti, kurią sudarė Samuelis Nigeris ir Zalmenas Reizenas, o paskui naujosiose Vilniaus kapinėse jam pastatytas paminklas: didžiulis erelis be vieno sparno. Tokių sekuliarių žydiškų paminklų Rytų Europoje dar buvo reta. Tarpukario Vilniaus žydų inteligentams jis tapo svarbiu memorialu.[2]

Mano mamos patirtas atminties aktas buvo išvien agresyvus. Ji greičiausiai galvojo: „Nekiškite rankų prie mano dainos! Kitaip negu jūs, aš dar nepraradau tikėjimo. Velniop jus, aš kraustausi lauk iš čia!“

- Litvakai yra aistringi žmonės. Gal jie ir atrodo rimti bei mokslingi, bet už tos ramybės ir susilaikymo slypi ištisi emocijų – ir atsidavimo – klodai.

- Litvakai gerbia poetus. Vaiteris labiausiai buvo žinomas kaip dramaturgas, bet Reizenas nesuklydo įamžinęs jį kaip poetą. Sakyčiau, kad Lietuvoje vienam gyventojui teko daugiau jidiš kalba rašiusių poetų negu bet kuriame kitame Rytų Europos regione. Pateiksiu jums 15 didžiųjų poetų litvakų sąrašą, kur „didysis“ reiškia „tas, kuris naujaip pavartojo jidiš kalbą ar sukūrė naujas poezijos formas“. Pateikiu sąrašą pagal poetų gimimo datą:

- Morrisas Rozenfeldas (iš Bokšių kaimo Suvalkų apskrityje)

- Jehoašas (iš Virbalio)

- Avromas Reizenas (iš Koidanovo, dab. Džiaržynskas, Baltarusija)

- Juozapas Rolnikas (iš Žukovico)

- Leivikas (iš Igumeno, dab.Červenė Baltarusijoje)

- J. Švarcas (iš Petrašiūnų prie Kauno)

- Anna Margolin (iš Bresto-Litovsko)

- Cilė Dropkin (iš Babruisko)

- Kadia Molodovski (iš Berezos Kartuskos)

- Leibas Naidusas (iš Gardino)

- Moišė Kulbakas (iš Smurgainių)

- Samuelis Halkinas (iš Rahačovo)

- Chaimas Grade (iš Vilniaus)

- LeizerisVolfas (iš Vilniaus)

- Avromas Suckeveris (iš Smurgainių)

Tikriausiai pastebėjote, kad trys iš penkiolikos yra poetės moterys. 1980-aisiais pradėjus kilti žydiškojo feminizmo bangai jų darbai susilaikė daug dėmesio, nors litvakiška kilmė daug kam praslydo pro akis. Tiesą sakant, aš ir pats nustebau tai sužinojęs.

Kai Rytų Europos žydės moterys ėmė drąsiau ir garsiau reikštis (o pas mus mano mamos balsas tikrai nebuvo iš tyliųjų), ėmė plisti ir įvairaus politinio bei socialinio pobūdžio žydų jaunimo judėjimai, kurių dėka žydai paaugliai taip pat įgijo savą platformą. Tarpukariu dauguma Lenkijos ir Lietuvos žydų paauglių priklausė vienokiam ar kitokiam judėjimui. Vienas toks paauglys buvo Icchokas Rudaševskis, aistringas pionierius ir aktyvus Jaunimo klubo Vilniaus gete narys. Pradėdami kiekvieną Jaunimo klubo susitikimą, jo nariai sugiedodavo šį himną, kuriam žodžius parašė Vilniaus geto poetas Šmerelis Kačerginskis, o muziką sukūrė Basė Rubin:

,אונדזער ליד איז פול מיט טרויער

;דרײַסט איז אונדזער מונטער גאַנג

,כאַָטש דער שונא וואַכט בײַם טויער

!שטורעמט יונגט מיט געזאַנג

,יונג איז יעדער, יעדער

,יעדער ווער עס וויל נאָר

!יאָרן האָבן קיין באַטײַט

,אַלטע קענען, קענען,

קענען אויך זײַן קינדער

!פון א נײַער, פרײַער צײַט

Liūdesys dainoj mūs skamba

Žengiame žingsniu narsiu;

Nors už vartų tyko priešas,

Jauni veržias su balsu:

Jie jauni, jauni,

Jauni, kas nori,

Ir jų amžius – ne kliūtis!

O senieji

Atjaunės vėl,

Kai laisvi laikai ateis!

Ar tyčia, ar atsitiktinai, bet Kačerginskio dainos priedainyje, “yung iz yeder, yeder, yeder ver es vilnor…(jie jauni, jauni, jauni, kas nori…) ataidi Vilniaus Gaono posakis: Vil-nor, vestu vern a goen.

Štai ką Rudaševskis užrašė savo dienoraštyje1943-ųjų sausio 28 d.:

Vakare dalyvavau įdomiame literatūros būrelio susitikime. Jaunas poetas Avromas Suckeveris papasakojo mums apie jidiš kalba rašiusį poetą Jehoašą ir padeklamavo jo, Jehoašo, eilėraščių. Gamtos aprašymai mums padarė itin didelį įspūdį. (…) Mes nusprendėme suorganizuoti Jehoašo poezijos vakarą ir jam skirtą parodą. Kadangi Suckeveris dirba YIVO, jam pavyko išgelbėti daug vertingų objektų, tokių kaip laiškai ir rankraščiai.[3]

Įkvėpti to, ką sužinojo, Jaunimo klubo nariai nusprendė pasidalinti savo naujai atrasta meile poetui Jehoašui su viso geto gyventojais. Jie paprašė Suckeverio įrengti Jehoašui skirtą parodą klubo patalpoje. Kaip Popieriaus brigados narys, priverstas dirbti Žydų mokslo instituto YIVO pastate ir padėti vokiečiams nuosekliai grobstyti žydų kultūros lobius, Suckeveris galėjo prieiti prie reikalingų objektų.[4] Bet ši operacija buvo sudėtinga, nes viską reikėjo iš YIVO pastato, kuris buvo vokiečių pusėje, slapta nuo pastarųjų prasinešti į getą. Štai kaip parodos atidarymą 1943-ųjų kovo 14-ąją savo dienoraštyje aprašo Rudaševskis:

Šiandien mūsų klube vyko Jehoašo šventė ir jam skirtos parodos atidarymas. Paroda neįtikėtinai graži. Visa klubo skaitykla pilna medžiagos apie poetą. (…) Vos tik įėjęs iškart pajunti visaapimantį jaunatvišką užsidegimą. Visas pateikimas spinduliuoja jaunatvišką energiją. Viskas taip kultūringa ir miela akiai. Ten įėję žmonės išsyk užmiršta, kad yra gete. Šioje parodoje yra daug vertingų dokumentų, tikrų lobių: Pereco rankraščiai, kuriuos jis siuntė Jehoašui, paties Jehoašo ranka rašyti laiškai. Yra retų iškarpų iš laikraščių. Biblijos vertimams į jidiš kalbą skirta parodos dalis turi net XVII amžių siekiančių jidiš vertimų. Kai pažiūri į eksponatus, į mūsų triūsą, pasijunti išties įkvėptas ir iš tikrųjų užmiršti esąs tamsiame gete. Šventė taip pat vyko nuostabiai. (…) Mūsų vaikai skaito rašinius apie Jehoašo poeziją, apie Jehoašą kaip grožį, muziką ir spalvas skelbusį poetą. Šventės metu visų nuotaika buvo išties pakili. Tai buvo tikros atostogos, jidiš kalba rašytos literatūros ir jidiš kultūros manifestacija.[5]

Holokausto metraščiuose Jehoašui skirta paroda buvo vienetinis įvykis, kurio unikalumas didžiąja dalimi kilo iš kultūrinio litvakų paveldo. Nors gete tebuvo likę vos 20 000 žydų, mažas anksčiau didžios bendruomenės likutis, šioje parodoje pademonstruotos būtent tos vertybės, kurias Avromas Suckeveris siekė išsaugoti. Ji iliustruoja tai, ką Vilniaus geto penkiolikmetis galėjo išmokti iš Saliamono Bliumgarteno, žinomo Jehoašo slapyvardžiu, kuris iš Lietuvos emigravo į JAV 1890-aisiais, būdamas 18 metų, įsikūrė Niujorke ir mirė ten 1927-aisiais.

- Meilė kraštovaizdžiui. Jehoašas buvo pirmasis didis poetas, apie gamtą rašęs jidiš kalba – ne apie gimtosios Lietuvos gamtą, o apie Amerikos gamtą, kurioje įsikūrė vėliau. Jo atliktas Henrio Wadswortho Longfellow poemos „Hiavatos giesmė“ vertimas buvo puikiai įvertintas ir atskleidė, kaip pasinaudojant jidiš kalba galima priimti niekada iki tol nepažintą pasaulį. Per Jehoašo eiles Suckeveris parodė savo studentams, kad negalima nutraukti ryšio tarp žydų ir jų aplinkos – kadangi pats Suckeveris buvo iškiliausias apie gamtą jidiš kalba rašęs poetas, jis prieš pat įsiveržiant vokiečiams sukūrė naują kalbą Lietuvos miškų ir laukų grožiui apdainuoti. Knygą jis pavadino Valdiks, Miškinė. Suckeveriui gamta išliko grožio, poezijos, meninio įkvėpimo ir kūrybinio atsinaujinimo šaltinis. Surengdamas parodą Suckeveris parodė visiškai atskirtai nuo išorinio pasaulio žydų kartai, kad gamta yra – cituojant Rudaševskį – „grožio, muzikos ir spalvų“ šaltinis.

- Atgal prie Biblijos. Jehoašas labiausiai išgarsėjo atlikęs Biblijos vertimą, prie kurio darbavosi daugybę metų ir kuris, pačiam poetui dar esant gyvam, patapo gyvąja klasika. Šis didingas pasiekimas, kaip atskleidė paroda, pats buvo grandis ilgoje Biblijos vertimų į jidiš kalbą grandinėje, kurios ištakos siekė spaudos išradimą. Kas aiškiau parodo litvakų paveldą negu meilė Torai ir zitsfleysh, užsispyrimas, be kurio neišversi Mozės Penkiaknygės, Pranašų ir Raštų? Jehoašas buvo pavyzdinis litvakas, kadangi jo mąstymas buvo pakankamai tvarkingas atlikti šiuolaikinį Hebrajų Biblijos vertimą, pagrįstą lyginamąja Artimųjų Rytų filologija ir moderniomis Biblijos studijomis, vertimą, kuris išsaugotų khumesh-taytsh, žodinės aškenazių Biblijos studijų tradicijos, tarseną ir sintaksę, bet taip pat skambėtų jidiš kalbos grožiu, muzika ir spalvomis. Litvakai garsėjo savo Toros studijomis ir, nors Jehoašas iš namų išvyko būdamas viso labo 18 metų, tą paveldą jis su savimi nusivežė į Naująjį Pasaulį, kur jo hebrajų ir jidiš kalbomis išleistas dvitomis tapo vertingiausiu dalyku Amerikos žydų namuose. Yehoašo dėka net ir tokie radikaliai sekuliarūs žydai kaip Icchokas Rudaševskis tiesiogiai susipažino su Knygų knyga.

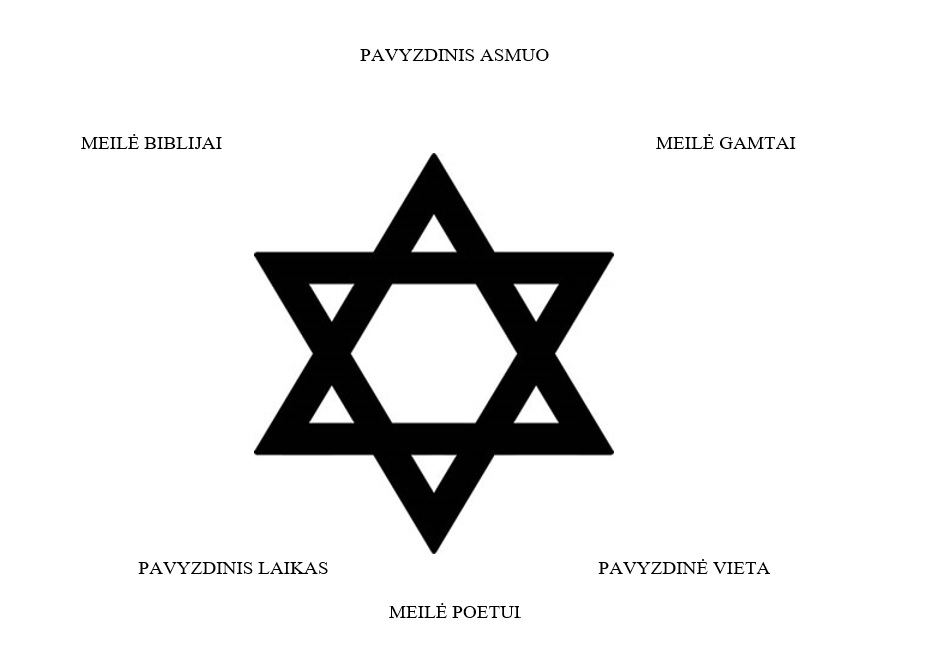

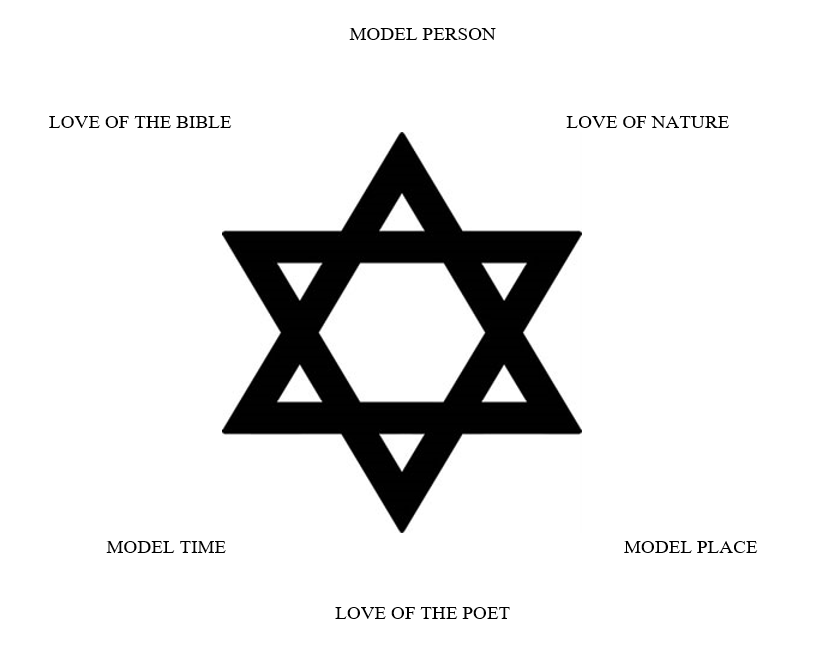

Padedami dviejų mūsų informantų, Mašos Roskies ir Icchoko Rudaševskio, jau esame pasirengę nubraižyti kolektyvinės žydų atminties DNR diagramą. Ant trinarės „pavyzdinio asmens, pavyzdinės vietos ir pavyzdinio laiko“ konstrukcijos dabar galime uždėti kitą trejetą, labiau būdingą litvakams. Antrasis trejetas atspindi naujus žydų savęs suvokimo būdus ir modelius, kurie ypač gerai išsivystė Lietuvoje. Čia labiau nei kur kitur pavyzdinis asmuo įgijo poeto pavidalą, pavyzdinė vieta išsiplėtė, apimdama gamtinį pasaulį, o pavyzdinis laikas bibliniame laikotarpyje buvo apibrėžtas iš naujo.

Štai kaip paprastai galime apjungti abu trikampius. Jei žiūri iš viršaus, išėjęs už laiko ribų, vienas jų užsikloja ant kito. Bet žiūrint iš istorinės perspektyvos reikėtų juos įsivaizduoti kaip vektorius, linkstančius vienas prie kito ir besitraukiančius vienas nuo kito. Lietuvoje priešingybės traukia, o tradicija ir modernybė gyvuoja šalia viena kitos. Prieštaravimuose litvakai tiesiog tarpsta. Jie žino, kaip sujungti dalykus, kurie visada iki tol buvo atskiri.

Apie tai, kad poetas tapo pavyzdiniu asmeniu, sužinojome iš Avromo Reizeno, apraudojusio A. Vaiterio mirtį, ir Abraomo Suckeverio, šventusio Jehoašo gyvenimą.

Apie tai, kad meilė gamtai įtvirtino vietos meilę, sužinojome iš Icchoko Rudaševskio reakcijos į Jehoašo apdainuotą gamtą ir iš Suckeverio sukurto būdo kalbėti apie gamtą.

Ir galiausiai apie tai, kad Biblija yra Meilės Knyga, galime sužinoti iš didaus litvako, pirmojo hebrajiškų romanų rašytojo, pirmojo, žydų kalba parašiusio šiuolaikinę meilės istoriją – Abraomo Mapu.

1853 m. parašytame romane Ahavat Tsiyon, Siono meilė, Mapu grąžino Biblijai Meilės Knygos ir Gamtos Knygos reputaciją, tuo pat metu visiems jauniems savo skaitytojams įskiepydamas neblėstančią meilę Sionui. Iš jo poetai litvakai išmoko, kaip geriausia išreikšti savo ryšį su žeme – pasinaudojant bibliniais vaizdiniais. Tiek, kiek kokia nors vietovė tapdavo namais, ji tapdavo ir Bibline Vieta.

Taigi pristatau jums šešių poetų sūkurį, šešeto iš penkiolikos, kuriuos jau paminėjau – jų poezija iliustruoja, kaip Biblija gali perkeisti, kaip Biblija tapo natūraliausia litvakų kalba. Jie pateikiami lietuvių ir jidiš kalba, su viltimi, kad juose jūs atrasite kažką pažįstama ir kažką visiškai neįprasta. Ir tikiuosi, kad šie eilėraščiai bent jau padės praplėsti įsivaizdavimą, kas vis dėlto yra litvakas.

Pradėsime nuo Leibo Naiduso, Gardine gimusio ir ten pat mirusio poeto. Kaip ir A. Vaiteris, jis atsimenamas kaip pačioje jaunystėje pakirstas poetas, nespėjęs realizuoti savo kūrybinio potencialo. Naidusas, jaunatviškiausias, romantiškiausias ir labiausiai dekadentiškas iš visų poetų litvakų, mirė būdamas 28 metų. Jo „Intymiose melodijose“ aprašomas išsilavinęs, pasaulietiškas žydas, kurį apkeri pašėlusi čigonė Dzeima. Šiais laikais toks eilėraštis būtų laikomas politiškai nekorektišku, nes neįmanoma nepastebėti, kiek jame orientalizmo. Bet tuo metu tokia atvira erotika bei įmantrus sapnų ir realybės, biblinių ir europietiškų peizažų mišinys sukėlė tikrą sensaciją. Atkreipkite dėmesį į nuorodas apie Artimuosius Rytus: Sidonas buvo finikiečių uostas, iš kurio nuodėmingoji karalienė Jezabelė į Izraelį atvedė pagoniškus ritualus. Ir pastebėkite frazę „mir dukht zikh, sapnuoju tave.“ Eilėraštis yra dabartyje vykstanti biblinė fantazija. Jei mokate jidiš kalbą, galėsite pasidžiaugti tokiais rimais kaip „Tsidn / Sidonas“ ir „midn / pavargęs“, arba pastebėti, kaip hebrajiškas žodis „pilegesh / sugulovė“ surimuotas su itin europietišku „elegish / eleginė“ – ir pasimėgauti tuo faktu, kad eilėraštį reikia skaityti lietuviškąja jidiš kalbos tarme, idant jis rimuotųsi.

Pailsusį ir geidulingą žvilgsnį myliu tavo,

Dzeima, ir juodas tarsi anglis plaukų bangas;

Ir tavo skarmalus, kurie iš pat Sidono atkeliavo,

Tarsi urvai dykumoje akis tavo tamsias.

Esi tokia graži, pašėlusiai eleginė, ilsiesi,

Šešėlį meta tavo antakių lankai;

Tave sapnuoju: liekna, jauna sugulovė

Iš tolimo haremo atvežta mane lankai.

Kh’hob lib, Dzeyma, dayn tayve-blik, dem farkhalesht-midn,

Di khvayles fun dayne lokn—shvarts vi keyl [koyl]

Dayne farbike trantes—tayere shtifn fun Tsidn,

Dayn fintseres eyg—a midbershe heyl.

Vi sheyn du bist, ven du ligst azey vild-elegish

Un a langer shotn falt fun dayn brem:

Mir dukht zikh: du bist a yunge, shlanke pilegesh,

Gebrakht ahertsu fun ergets a vaytn harem.

Visai kitaip biblinius siužetus atgaivina I. J. Švarcas poemoje Kentucky, kurią pradėjo rašyti 1918 m., išvykęs į Niujorką. Nieko panašaus – išskyrus Yehoašo „Hiavatos giesmės“ vertimą – skaitantieji jidiš kalba dar nebuvo regėję. Tai buvo pirmasis jidiš-amerikietiškas epas, įspūdingas savo plačia apimtimi tiek erdvėje, tiek laike. Jame pasakojama prekeivio Džošo istorija, kuris, kaip ir jo pirmtakas Jozuė, atvyko užkariauti Kanaano žemės, kuri Džošo atveju yra JAV pietūs ir pietryčiai, išsiskiriantys religingumu. Čia Džošas džiaugiasi savo „didžiąja paslaptimi“: tvarkomu namu, į kurį ruošiasi įsikelti su visa šeima ir kuris yra labiausiai apčiuopiamas įrodymas, kad ilgus metus Džošas ne veltui lenkė nugarą. Už pastangas epo herojui atlygina ir poetas, kuris nešykšti dėmesio gamtos grožiui ir jos dovanoms, ir pats Dievas. Džošas, kuris jau seniai nebepraktikavo žydų tikėjimo, sėkmės akimirką prisimena Izaoko maldą Dievui Pradžios knygoje: „Den oysgebreytert hot undz got / un mir‘n zikh farfestikn in land“ (Vert. A. Rubšys: „Šį kartą VIEŠPATS davė mums šiame krašte apsčiai vietos daugintis“).

Pro sutvarkyto namo langus

Laukų ir tolimų miškų platybė,

Pušinės grindys,

Nutviekstos šviesos,

Ant jų siūbuoja smailių lapų

Auksiniai ir žali šešėliai,

Senų ąžuolų ir jaunų ąžuolų,

Vos įstengė Džošas atsiplėšti

Nuo paslapties, kuri užpildė jį

Kaip vynas, neaprėpiama;

Ir stebint didžiąją platybę,

Prisiminė eiles senąsias:

„Šį kartą Viešpats davė mums

Šiame krašte apsčiai vietos daugintis.“

Litvakų poetų Biblijos interpretacija vienu svarbiu aspektu pagerino hebrajišką originalą: litvakiškoje interpretacijoje ne žydai taikiai sugyveno su žydais. Ar tai būtų čigonų stovykloje besibučiuojantys jauni Naiduso įsimylėjėliai, ar Džošo vaikai, netrukus susituoksiantys su kitų tautų ar kitų religijų atstovais, ar Moišės Kulbako epinėje poemoje „Raysn, Baltarusija“ aprašyti penkiolika karštakošių brolių. Dėdė Avromas ir gražioji Nastazija yra be galo įsimylėję, poemoje aprašyta, kaip meiliai jiedu bendrauja. Ir tik dvyliktoje – paskutiniojoje – strofoje Kulbakas aiškiai nurodo biblinę analogiją. Tai ne šiaip sielius Nemunu plukdantys du žydų valstiečiai. Tai – tikra žydų gentis, Baltarusijoje įsitvirtinusi taip, kaip jų protėviai buvo įsitvirtinę Pažadėtoje Žemėje. Mirties patale senelis suteikia palaiminimą savo sūnums – aprašant šią sceną naudojami vaizdiniai ir biblinės paralelės, kurios atliepia Pradžios knygos 49-ąjį skyrių (kur Jokūbas suteikia palaiminimą savo sūnums). Vyriausiasis Ortšė palaiminamas vietoje Reubeno, Rachmielis – tarsi jis būtų Juda, o Šmuilė – tarsi būtų Naftalis:

Tu, Šmuile, upininke, pasauly nėra kito tokio!

Šlapias esi visados ir virvę nešiojies suplukęs,

Atsiduodi žvynais ir perėmęs vandenio dvoką,

Palaimintas būki krante ir palaimintas būki ant upės.

Du Shmulye, der taykh-mentsh, nito af der velt aza glaykhn!

Bashtendik dem butsh af di pleytses, bashtendik a naser,

Geshmekt hot mit shupn fun dir, mit dem reyakh fun shleym in di taykhn,

Gebentsht zolstu zayn afn land, un gebentsht afn vaser.

Kulbakas tarsi paveldėjo šį įsišaknijimo jausmą, pojūtį, kad Baltarusijos upės ir laukai yra tikri jo namai. Jis kalba Biblijos įkvėptos šeimos balsu.

Kadia Molodovski augo visai kitokiuose namuose. Kitaip negu Kulbakas, poezija jai buvo būdas kalbėti savo tautai ir kalbėtis su savo tauta. Savo eilėraščių rinkinyje „Froyen lider, Moterų dainos“ ji klausė savęs, kas nutiktų toms nelaimingoms žydėms, kurios augo skurde, neteko namų, neužgyveno vaikų, nepatyrė meilės? Nelaimės valandą šios moterys tegalėjo atsigręžti į savo biblines pramotes: Sarą, Rebeką, Rachelę ir Lėją, kurias taip gerai pažino kalbėdamos tkhines, asmenines maldas, kurias moterys sakydavo jidiš kalba. Štai kokį vaidmenį galėjo vaidinti motina Lėja:

Toms, kur naktį verkia lovoj vienišoj,

Ir savo sielvarto neturi kam nunešti,

Sukepusiomis lūpomis šnabžda sau vienom,

Pas jas ateina motina jų Lėja

Ir uždengia blyškiais delnais pavargusias akis.

Tsu di vos veynen in di nekht af eynzame gelegers,

Un hobn nit far vemen brengen zeyer tsar,

Redn zey mit oysgebrente lipn tsu zikh aleyn,

Tsu zey kumt di muter Leye

Halt beyde oygn mit di bleykhe hent farshtelt. (1927)

Poetai litvakai, tiek vyrai, tiek moterys, laisvai galėjo gyventi Biblijoje, iš naujo ją pergyventi ir suprasti ją šiuolaikinio gyvenimo kontekste. Ryškiausiai ir įsimintiniausiai tai pavyko padaryti H. Leivikui ir Avromui Suckeveriui.

Iš visų biblinių pasakojimų nė vienas nepaliko tokio galingo įspaudo Leiviko religinėje vaizduotėje, kaip akeda, Izaoko aukojimas ant Morijos kalno. Personažų šiame pasakojime nedaug – tėvas, sūnus, balsas iš dangaus ir avinėlis – o rekvizitų dar mažiau – viso labo peilis ir altorius. Dar taupesnė Leiviko kalba, didingumu prilygstanti biblinei. Bet Leiviko supratimu, Izaoko aukojimo stebuklas slypi ne tame, kad šis paskutiniąją akimirką buvo išgelbėtas nuo mirties, bet pačiame aukojime, „der nes fun nesoyen, išbandymo stebukle“, žmogaus gebėjime pakelti kraštutinę kančią. Leiviko supratimu, būti žydu – tai stovėti pasirengus kitam kartui, kai tau į gerklę bus įremti peilio ašmenys. Kiekvienas trieilis posmas baigiasi tais pačiais žodžiais: „Un-vart, Ir laukia“.

Iš viršaus sušunka balsas

– Stok! – ranka ore sustingsta

Ir laukia.

Sutvinkčioja staiga gerklė gyslota

Išbandymo stebuklu

Ir laukia.

Nusineša jau tėvas sūnų.

Altorius lieka tuščias

Ir laukia.

Tarp spyglių įstrigęs avinėlis

Stebi ranką su peiliu

Ir laukia.

Derhert zikh fun oybn a bas-kol

—halt op!—blaybt di hant in gliver

Un—vart.

Git der haldz mit ale zayne odern

A tants inem nes fun nesoyen,

Un – vart.

Trogt der tate dem zun arunter,

Blaybt leydik un fray der mizbeyakh,

Un—vart.

Shteyt a lam in dornbush farflokhtn

Un kukt af der hant mitn meser

Un—vart.

Avromui Suckeveriui biblinė Atpildo diena buvo 1943-ųjų rugsėjo 12-oji, kai jis su žmona Freidke pabėgo iš geto drauge su antrąja kovotojų grupe ir prisijungė prie sovietinių partizanų brigados Lietuvos miškuose. Būtent todėl Suckeverio 24 eilučių ilgumo eilėraščiui „Di blayene platn fun Roms drukeray, Romų spaustuvės švino plokštės“ priskirta būtent ši data. Data atspindi labiau simbolinę negu tikrą eilėraščio sukūrimo dieną, kadangi poetinis kontekstas yra rašytojo kūrybos vaisius.

Vieną naktį pritrūkę kulkų jauni kovotojai įsilaužia į Romų spaustuvės pastatą, norėdami išlydyti švinines plokštes, kurios buvo naudojamos spausdinant Vilniaus Talmudą, įspūdingą Rytų Europos žydų kultūrinį pasiekimą. Šitai atkartoja gilioje senovėje įvykusį veiksmą – kai atgavę Jeruzalę Makabėjai pylė aliejų į Šventyklos žvakides, taip ir išlydytos švino plokštės su hebrajiškomis raidėmis buvo pilamos į kulkų liejimo formas. Alchemija pavyksta, kadangi paskutiniame posmelyje kovotojai žydai jau apsiginklavę, sukilimas įvykęs, o paskutiniosios geto valandos prilyginamos Jeruzalės apgulčiai. Kaip buvo sugriauta Jeruzalė, taip sunaikinta ir Lietuvos Jeruzalė.

Paskutiniame posmelyje du rimavimo būdai išryškina tolimos praeities ir herojiškos dabarties susijungimą. Vienas rimas paremtas germaniškais kalbos komponentais: HENT (rankos) – VENT (sienos) – DERKENT (atpažino). Kitas rimas paremtas hebrajiškais elementais jidiš kalboje. Žodį YERUSHALAYIM Suckeveris rimuoja su BLAYEN ir KLEZAYIN. Jis nukaldina tiesioginę ir tvirtą sąsają tarp Jeruzalės sugriovimo, plokščių švino ir ginklų, kuriuos Vilniaus partizanai naudojo savo paskutiniojo pasipriešinimo vokiečiams metu.

Ir tas, regėjęs žydus jų gražiausiais metais,

Kaip geto salėse ginklus jie ima –

Tas paskutinį Jeruzalės karį matė,

Didvyriškų sienų didvyrišką griuvimą;

Žodžius suprato tas, ir šviną liejo, nesant laiko,

Ir širdimi girdėjo: jų balsas iš senovės šaukia.

Un ver s’hot in geto gezen dos klezayin

Farklamert in heldishe yidishe hent—

Gezen hot er ranglen zikh Yerusholaim,

Dos faln fun yene granitene vent;

Farnumen di verter, farshmoltsn in blayen

Un zeyere shtimen in hartsn derkent.

Nesvarbu, kad tuomet švino plokštes jau seniai buvo išgrobstę vokiečiai, o sukilimas buvo nutrauktas tragiškomis aplinkybėmis. Žydų kolektyvinėje atmintyje ne tiek svarbu faktai, kiek jų reikšmė. Esminė eilutė poemoje, jos tiesos pagrindas, manau, buvo penktoji: „Mir, troymer, badarfn itst vern soldatn! / Mes, svajotojai, turime tapti kareiviais!“. Kaip – domėjosi Suckeveris – iš tokių bejėgių žmonių galėjo atsirasti tiek pasipriešinimo kovotojų? Simboline poezijos kalba jis parašė pačia savo esme litvakišką atsakymą į šį klausimą.

Ši žydų jaunimo karta buvo išauginta didžios civilizacijos. Jų kilmė pažymėta mokslo, religinės disciplinos ir idealizmo. Jiems tereikėjo stebuklingo užkalbėjimo, rakto, nenugalimo troškimo, jie teturėjo vienokią energiją paversti kitokia. Pažindami savo istoriją šie žmonės sugebėjo parašyti naują ryškų jos skirsnį. Jei vertintume nepasisekusį sukilimą partizaninio karo istorijos kontekste, jis nusipelnytų ne ką daugiau negu išnašos. Bet žydų tautos metraštyje ginkluotas pasipriešinimas vokiečiams atspindėjo didžiausią proveržį žydų sąmonėje po Makabėjų sukilimo.

***

Ką reiškia būti litvaku? Tai reiškia dainuoti:

Gražiausios dainos,

Melodijos gražiausios,

Nedainuoki jų, kai šypsosi sėkmė,

Dainuoki nuopolio metu.

Bet tai reiškia dainuoti ir tai:

Jie jauni, jauni,

Jauni, kas nori,

Ir jų amžius – ne kliūtis!

O senieji

Atjaunės vėl,

Kai laisvi laikai ateis!

Šalia to, kad įdarytą žuvį pagardindavo pipirais, o ne cukrumi, ir šalia išdidžios stiprių moterų eilės, ir šalia tseleym-kep, eretikų reputacijos, litvakai gyveno su ypatingu atsidavimu: atsidavimu praeičiai, dvasiniams vadovams, bendruomenei, Knygų knygai, gamtos grožiui ir poetiniam žodžiui.

(vertė Miglė Anušauskaitė)

[1] Žr. straipsnį “The Geography of Yiddish” knygoje The Shtetl Book, sudar. Diane K. Roskies and David G. Roskies (New York: KtavPub. House, 1975)

[2] Žr. http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Vayter_A, ten yra nuoroda į nufilmuotą Cemacho Šabado laidotuvių ceremoniją, kurios metu kalbos buvo sakomos šalia Vaiterio paminklo.

[3] Iš katalogo Avraham Sutsḳeṿer bi-melot lo shivʻim: taʻarukhah = Avraham Sutsḳeṿer tsu mṿern a benshivim: oysshtelung, kurį parašė ir sudarė Abraomas Noveršternas. Jerusalem: TheNationaland University Library, 1983, p. 140.

[4] Žr. David E. Fishman, Shaytlekh aroysgerisn fun fayer : dos oprateven yidishe kulṭur-oytsres in Ṿilne. New York: YIVO, 1996.

[5] Avraham Sutsḳeṿer bi-melot lo shivʻim, ten pat.

EN:

Litvaks in Love

David G. Roskies

Tyszkiewicz’s Palace on the corner of Troky and Plylimo (formerly Zavalna), is an architectural landmark, especially its outer façade. The two neockassical half-naked tosros holding up the balcony are vivid reminders of the Polish aristocracy who once lived and ruled here in the 18th century. They link Vilnius to a pan-European architectural movement that looked to Ancient Greece for inspiration.

Tyszkiewicz’s Palace has passed through many hands since then. When I first visited Vilnius in 1971, it housed the Soviet Polish Academy. There was no question of goinfg inside. “Ze notr ze,” my guide Zalman Gurdus said to me, “ale yidn hot men oysgeharfet, ober di tsvey bulvanes shteyen nokh; all the Jews were murdered, but the two bulvanes are still standing.” That was the comical name used by the Jews of Vilna to refer to this local landmark.

By my second visit, in 2000, the Soviets were gone, the front door was open, and the porter, still sitting in the old booth, was happy to let us in. The property had just been acquired by Vilnius University, but renovations had not yet begun. The building looked very run down. The linden trees were gone. They had been cut down for firewood during the war. I sat in the huge courtyard for a long time, telling Shana, my wife, our friends Monika and Staszek from Warsaw and our local guide Ilya all the stories I knew about the Jewish inhabitants of this place during the time when my mother lived trhere, from 1906-1930, when it was also home to Kochanovski’s Kindergarten, the Matz Press, a Jewish orphanage, Badaness’s Bakery, and much more.

Yesterday, I went back and was impressed but what the University has built. It is a model, as yet unfinished, of urban renewal. But as we passed through the automatic doors and walked up the steel and open staircases, my mind was somewhere else. For me, this place does not live in history, or architecture, or urban renewal. It exists in memory alone. In memory, it belongs within a separate geography and another time zone. In memory, the two bulvanes mark the entrance to Yiddishland, and to a place where Litvaks were very much in love.

So I invite you to join me on a Jewish tour of my favorite collective memory-sites.

Who’s taking you on this tour is a cultural historian. I became a cultural historian for two reasons:

One has to do with being a Litvak. Being a Litvak lies at the core of my Jewish identity. For me as for other Litvaks, “Lita” is a separate and autonomous geographic-cultural entity. It is an LU [Litvak Union] within the EU! To be a Litvak is to have a passport for life; it is good anywhere: in South Africa, Australia, Canada, Crown Heights, St. Petersburg, or Tel Aviv. It is a very particular way of being a Jew; both a privilege and a set of expectations. A Litvak is a thorn in everyone’s side. There’s a reason why Litvaks season their gefilte fish with pepper and not with sugar.

Another has to do with my being a feminist. I descend from generations of matriarchs. Many Jewish families that hail from Lita derive their names from a matriarchal figure: Syrkis, Syrkin (=Sorke, Sarah), Rivkin (=Rivke, Rebecca), Brokhes (=Bracha), Reines (=Rayne). So too, Roskies, which comes from some great-great grandmother whose name was Royz, Rose. Her children were known as Royzkes kinder. Royzkes became Roskes became Roskies.

My mother tongue is Yiddish. Although my parents spoke four other languages, Yiddish became the language of the home after my parents escaped from Europe and arrived in the safe haven of Montreal, Canada. I was extremely attached to my mother. In large part, it is because of her that I dedicated my life to Yiddish.

My mother, born in Vilna, and my father, born in Białystok, spoke Litvish, i.e., Lithuanian Yiddish, one of the three main dialects.

And finally, I married a fellow Litvak.

Using the tools of a cultural historian, drawing upon my Litvak identity and turning feminism into a source of knowledge, I think I have successfully cracked the DNA of Jewish collective memory. I know what it is, and I know how it works.

Jewish collective memory is organized around saints, sanctuaries, and sacred times. In this way, each generation of Jews shaped the model life, the model community, and the model time. You don’t have to be a Litvak to unlock the DNA of Jewish collective memory, but it certainly helps, because Lita is where this triple axis, this three-pronged model, emerged in bold relief. This model was so stable that it remained in place even when the world began to change.

In Lita, things really began to change with the rise of the religious revival movement called Hasidism at the end of the eighteenth century. So long as Hasidism was limited to Podolia and Volhynia, which after all, were located south of the “Gefilte Fish Line”[1] and where people spoke a different Yiddish, there wasn’t much to worry about. OK. So there was talk of a new culture hero named Israel Baal Shem Tov, better known as the Besht. He was a faith healer, a zaddik, or saintly person, who engaged in all manner of non-Litvak behavior: an effective preacher and teacher, he came in conflict with renowned Torah scholars, the elite of traditional Jewish society. Worse yet, he popularized the study of the Kabbalah, claimed to have paid periodic visits to heaven, and encouraged mystical prayer, performed with bizarre and ecstatic song and dance at all hours. Then, before you knew it, hasidic prayer houses were beginning to appear in Lita, too. The time had come for the rabbinic establishment to take

There was only one person who could stand up to this new model of spiritual leadership and that was Elijah son of Solomon Zalman in whose honor the title of Gaon was resurrected after a break of four hundred years. As the Besht became the founding father of Hasidism, the Vilna Gaon became the founder of the Opponents, the Misnagdim. But while the origins of Hasidism are still shrouded in legend, we know with absolute precision when and how the Misnagdic countermovement came into being. It happened in 1772, when for only the second time in his life Elijah entered the shtotshul, the Great Synagogue, in Vilna. There he read aloud the excommunication decree against the Hasidim. (The first time had been when he delivered a talmudic discourse there at the age of six and a

In Jewish collective memory, the text of the herem, the excommunication decree, does not loom nearly as large as Martin Luther’s “Ninety-five Theses.” Most people, including me, have never read it. The Gaon of Vilna’s memory is revered in other ways. His influence spread far and wide through two portable memory-sites, one elite, the other popular. In elite circles, no edition of the Shas, the Babylonian Talmud, was complete without Hagahot HaGra, his textual glosses and emendations that appeared in the margins of the folio-sized page, especially since the Vilna Shas published by the Widow Rom and her Sons became the gold standard of the Babylonian Talmud. This made the Vilna Gaon a timeless textual presence. The Gaon’s fame was also embodied in a popular medium that he would doubtless have frowned upon: His portrait hung in Jewish homes throughout Eastern Europe—and beyond. If you Google him, you can choose between the one in which he is wearing his tallit, or prayer shawl, and tefillin, phylacteries, on his head, or a fancy black ecclesiastical hat.

But more important for our purposes are the oral traditions that have been passed down in his name. Once, Rabbi Elijah was approached by a congregant, who asked him: “Tell me Rabbi, how does one become a Vilna Gaon?” The Gaon replied: “Vil-nor, vestu vern a goen, want it badly enough, and you too will become a Gaon.” Do not depend on a miracle. Do not look to the zaddik to do the work for you. Work to fulfil your own personal ambition. This is the essence of the misnagdic-Litvak Torah: Vil-nor.

The contest over the model person, however, did not end here. In addition to Misnagdim and Hasidim, who remained locked in opposition for over a century, a new group made its presence felt, who were called Maskilim, enlighteners, tseylem-kep. A tseylem-kop is someone suspected of harboring a crucifix in his head. He’s too smart for his own good. He is willing to sacrifice piety for the sake of free thought. Lita soon became a center of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment.

Unlike a zaddik or a misnagdic rabbi, a leader who stood-in for the collective, who was deeply enmeshed in communal life, a Maskil was very much of a loner, an outcast, a heretic. Worse yet, a Maskil made his rebellion the subject of something called an autobiography, based on a new literary genre invented by Jean Jacques Rousseau. The first to adopt the Rousseauian model—wouldn’t you know it?— were Litvaks: Shlomo ben Joshua from the town of Zhukov Borok near Mir in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, who changed his name to Solomon Maimon and published his Lebensgeschichte, in faulty German, when he was all of 38 years old; and Mordecai Aaron Ginzburg, born in Salantai (near Kaunas), who wrote in Hebrew. Whether they remained in Lita or moved to Germany, the center of Enlightenment, what Litvak autobiographers had in common is that they were married off at a very young age to a girl they didn’t love and were miserable for the rest of their lives.

So the model person now existed in three competing and vastly different types. But all Jews everywhere agreed that the model place was Jerusalem, the site of the First and Second Temples. It followed, therefore, that in Jewish collective memory, Jerusalem became the template of the Kehilla Kedosha, the Covenantal Community. Whatever claim a Jewish community had to being an “ir va’em beYisrael, “a City and Mother in Israel,” had to derive from its ancient pedigree. The model place was a place suffused with the presence of God.

Vilna’s claim to be the Jerusalem of Lithuania rested upon the presence of the Great Synagogue. Like the Temple in Jerusalem, the full splendor of the Vilna shtotshul was evident only from the inside, because a third of it was built below ground level. It was big enough to seat 3000 people.

Like the Temple in Jerusalem, most of the treasures of the Great Synagogue were plundered, time and time again. First erected at the end of the 16th century, it was attacked and burned three times by the students of the Jesuit academy and their willing accomplices. The permanent structure was rebuilt after the last pogrom of 1635. Like the Temple, the Great Synagogue was finally destroyed by the world’s greatest tyrants. Hitler partially destroyed it in 1943, and Stalin finished the job, in 1945. Like the Temple, it was the site of miracles.

The third and last time that Rabbi Elijah entered the shtotshul was in 1794, when the Russian army bombarded Vilnius, which then belonged to Poland. The shtotshul was built to withstand attack and the 72-year-old Gaon ordered the entire Jewish population to take refuge inside its walls. He then opened the Aron Koydesh, the Holy Ark containing the scrolls of the Torah, and recited seven times the 20th chapter of Psalms

For the leader.

A psalm of David

May the Lord answer you in time of trouble,

the name of Jacob’s God keep you safe.

May he send you help from the sanctuary

and sustain you from Zion….

May the LORD answer us when we call.

:א לַמְנַצֵּ֗חַ מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִֽד

:ב יַֽעַנְךָ֣ יְ֭הוָה בְּי֣וֹם צָרָ֑ה יְ֝שַׂגֶּבְךָ֗ שֵׁ֤ם אֱלֹהֵ֬י יַעֲקֹֽב:

…:ג יִשְׁלַֽח-עֶזְרְךָ֥ מִקֹּ֑דֶשׁ וּ֝מִצִּיּ֗וֹן יִסְעָדֶֽך

:י יְהוָ֥ה הוֹשִׁ֑יעָה הַ֝מֶּ֗לֶךְ יַעֲנֵ֥נוּ בְיוֹם-קָרְאֵֽנוּ

after which the entire congregation—men, women, and children—repeated the chapter seven times. Just then, the roof was hit by a cannonball that instead of exploding remained lodged therein. The Jews were terrified, but the Gaon hushed them and said: “Botl, botl di gzeyre. The evil decree has been annuled.” Even as the Gaon spoke, the Polish military decided to open the city gates to the Russians rather than risk having the whole city destroyed. Ever after, a prayer of thanksgiving was offered up each year on that date and the congregation collected a special donation for having been saved from death.

If you’re a Litvak, this is the perfect miracle, because it allows for two different explanations. On the obvious level, the prayers offered up by the Gaon of Vilna are what saved the Great Synagogue from destruction. Only those prayers led by that spiritual giant could have stopped the cannonball from exploding. Less obviously, it was the prudent decision of the Polish, temporal rulers, to open the gates.

On the site of the Gaon’s house the Kahal, or Jewish Community Council, built a kloyz, a combination study and prayer house, in 1800, five years after he died. What kind of memory-site was this kloyz? It embodied the piety and extreme asceticism of the man himself. In Vilna as nowhere else, the model person and the model place were combined into one.

Opened nearby in 1902 was the Strashun Library with the thousands of Hebrew texts and manuscripts, including religious writings, fiction, poetry, scientific works, Jewish and Karaite historical works, travel accounts, and Hasidic texts collected by the prominent Vilna Maskil Matisyohu Strashun. And so, the model Litvak place was one that combined enlightenment and traditional piety, secular knowledge and Torah learning. Litvaks moved around a lot; wherever they went, they took a piece of Lita with them. In America, another group of hard-core Litvaks—Bernard Revel, Samuel Belkin and Joseph Soloveitchik—created a formal framework called Torah uMadda (Torah and Science) to foster a permanent presence for this model in the New World. Today it is known as Yeshiva University. Meanwhile, as early as 1834, a group of young Maskilim, reform-minded Jews, in Vilna banded together to form Tohoras Hakoydesh, the first Jewish prayer group in Eastern Europe to insist upon decorum: No talking during shul! That’s Litvaks for you.

What about the model time? If you were a Hasid, the model time was when the zaddik was still alive and miracles were still wrought in Israel. If you were a Misnagid, you knew that only a great rabbinic leader could save a Jewish community from destruction. The Great Synagogue was spared because the Holy Congregation upheld its covenantal relationship with God. As for the Maskilim, since they believed in the emancipation, they had a linear, progressive concept of time. Today was better than yesterday; tomorrow would be even better.

As I said, you don’t have to be a Litvak to unlock the DNA of Jewish collective memory, but it certainly helps, because Lita was the ideological battleground where the competing models of the ideal person, the ideal community and the model time were laid out most starkly. Thus far, however, we’ve been looking through a male-dominated lens. The problem with rabbis, zaddikim and Maskilim, for example, is that they all tend to be male. And the same is true for synagogues, libraries and yeshiva universities, which once again are for the most part the domain of men. What happens when you look at Jewish and Litvak cultures through a feminist lens? Feminism is an egalitarian pursuit. It begins by asking: Who has been excluded? And the obvious answer is that there can be no collective memory without the women, the children and the young. Memory begins in the home and school; at family gatherings and youth groups.

***

It was the middle of the war. My parents, Masha and Leyb Roskies, who had managed to escape from Europe in 1940 with my brother Ben and sister Ruth, were attending a wedding at a synagogue in Westmount, the fashionable and exclusive area of Montreal, Canada, where they were then living.

As the bride starts walking down the aisle, the musicians strike up Mendelssohn’s “Song Without Words,” and my mother is shocked. How could they have chosen to play that very melody?

Since the pogrom of April 1919, when Polish Legionnaires dragged the playwright A. Vayter out into the street and shot him at point blank, right through his girlfriend who was trying to shield him with her body, that melody had become her sacred hymn. It had been set to words by the Yiddish poet Avrom Reisen and at the funeral all the youth of Vilna and all the leaders of the community walked behind the bier and sang:

The loveliest songs, the loveliest melody,

Do not sing them when fortune’s rising,

Sing them during decline.

Ring out, sounds of glory,

Though the spring has passed us by,

Though the sun has long since set

Though the poet is dead.

,די שענסטע לידגעזאַנגע

,די שענסטע מעלאָדי

,ניט זינג בײַם בליִען

.נאָר זינג בײַם אונטערגאַנג

,קלינגט זשע הויך, איר שיינע קלאַנגען

,כאָטש דער מײַ איז שוין פֿאַרבײַ

,כאָטש די זון איז שוין פֿאַרגאַנגען

.כאָטש דער דיכטער איז שוין טויט

My mother was 13 years old at the time, a very impressionable age, and although Russian, not Yiddish, was the language of her home, Masha committed the lyrics to memory. Another reason this song loomed so large was that one of her half-sisters was a close friend of Vayter’s girlfriend, the one who tried to shield him with her own body. That is what you do when you love someone, she would later explain to her mizinik, her youngest offspring. You sacrifice yourself on their

Angry at the profane and seemingly frivolous manner in which this sacred hymn was being used by the rich Jews of Westmount, in the very midst of a war in which millions of our people were being annihilated, my mother made a momentous decision. She decided to leave that neighborhood and relocate her family to a Yiddish-speaking part of town. Other decisions followed: to enroll my brother in the Folkshule, a Yiddish-Hebrew dayschool, and to dedicate the rest of her life (and my father’s discretionary income) to supporting Yiddish writers and

My mother’s story and song have three important lessons to teach us about what it means to be a Litvak.

- Memory is an aggressive act. This has nothing to do with nostalgia, whose purpose is to ease the pain, to overcome the loss, by imagining a past more in harmony with the present. Although Reisen’s lyrics make no mention of historical events, they do evoke the senseless loss of Vayter’s creative spirit. This song was followed by the Vayter-bukh, a memorial volume in his memory published under the editorship of Shmuel Niger and Zalmen Reyzen, followed by the erection of the Vayter Monument in the new Vilna cemetery: a huge eagle with one wing missing. Such secular Jewish monuments were still a rarity in Eastern Europe. It became a major memorial site for the Vilna Jewish intelligentsia between the two world wars.[2]

My mother’s memory, of course, was nothing if not aggressive. “Don’t you dare mess with my song!” is what she must have been thinking. “Unlike you, I still keep the faith. Damn you. I’m moving out of here!”

- Litvaks are passionate people. They may look serious and studious, but beneath that calm and restraint there lurks a world of emotion—and devotion.

- Litvaks revere their poets. A Vayter was primarily a playwright, but Reisen was not wrong to memorialize him as a poet. Per capita, I would say, Lita produced more great Yiddish poets than any other region in Eastern Europe. Here is a list of fifteen major Litvak poets, and by “major” I mean a poet who took the Yiddish language and the craft of poetry in new directions. I list them in their order of birth:

- Morris Rosenfeld (from the village of Boksze in the Suwalki district)

- Yehoash (Virbalis)

- Avrom Reisen (Koidany)

- Yoysef Rolnik (Zhukhovits)

- Leivick (Ihumin)

- J. Schwartz (Petroshun, near Kovno)

- Anna Margolin (Brisk-de-Lite; Brest-Litovsk)

- Celia Dropkin (Bobruisk)

- Kadia Molodowsky (Bereza Kartuskaya)

- Leyb Naydus (Grodno)

- Moyshe Kulbak (Smorgon)

- Shmuel Halkin (Rogachev)

- Chaim Grade (Vilna)

- Leyzer Volf (Vilna)

- Avrom Sutzkever (Smorgon)

You will note that three of the fifteen are women poets. Since the rise of Jewish feminism in the 1980s, their work has generated a great deal of interest, though their common Litvak origin seems to have escaped notice. To be honest, it came as a surprise to me as

As Jewish women began to make their voices heard in Eastern Europe (and in our home, my mother’s voice could be heard loud and clear), Jewish adolescents were also given a voice through the spread of Jewish youth movements, covering the entire political and social spectrum. Between the two world wars, the majority of Jewish youth in Poland and Lithuania belonged to one or another movement. One such adolescent was 15-year-old Yitskhok Rudashevsky, an ardent Pioneer and an active member of the Youth Club in the Vilna ghetto. Every meeting of the Youth Club began with the singing of this hymn, which was written by the ghetto poet Shmerke Kaczerginski, and set to music by Basye Rubin:

,אונדזער ליד איז פול מיט טרויער

;דרײַסט איז אונדזער מונטער גאַנג

,כאַָטש דער שונא וואַכט בײַם טויער

!שטורעמט יונגט מיט געזאַנג

,יונג איז יעדער, יעדער

,יעדער ווער עס וויל נאָר

!יאָרן האָבן קיין באַטײַט

,אַלטע קענען, קענען

קענען אויך זײַן קינדער

!פון א נײַער, פרײַער צײַ

Our song is filled with grieving,

Bold our step, we march along.

Though the foe the gateway’s watching,

Youth comes storming with their song:

Young are they, are they, are they

Whose age won’t bind them,

Years don’t really mean a thing,

Elders also, also, also, can be children

In a newer, freer spring.

Whether consciously or not, Kaczerginski’s refrain, “yung iz yeder, yeder, yeder ver es vil nor…, young are they, are they, are they who so wish to be,” resonates with the Gaon of Vilna’s catchphrase: Vil-nor, vestu vern a

So here is what Rudashevsky recorded in his diary on January 28, 1943:

In the evening I attended an interesting literary study-group. The young poet Avrom Sutzkever told us about the Yiddish poet Yehoash, and recited his, Yehoash’s, poems. We were particularly inspired by the nature descriptions ….We decided to organize a Yehoash Evening and Yehoash Exhibition. Because he works at the YIVO, Sutzkever managed to rescue many valuable objects, like letters and manuscripts.[3]

Inspired by what they had learned, the members of the Youth Club decided to share their newfound love for Yehoash with the ghetto at large. They asked Sutzkever to mount a Yehoash Exhibition in their auditorium. As a member of the Paper Brigade, forced to work in the YIVO building to help the Germans with the systematic plunder of Jewish cultural treasures, Sutzkever had access to the necessary artifacts.[4] But this was a complicated, clandestine operation, because all the materials had to be smuggled into the ghetto from the YIVO, which was located on the Aryan Side, and the exhibition itself had to be kept secret from the Germans. Here is how Rudashevsky describes the opening in his diary on March 14, 1943:

Today the opening of the Yehoash Celebration and Yehoash Exhibition took place in our club. The exhibit is spectacularly beautiful. The whole reading room in the club is filled with materials…The moment you walk in, you sense the youthful zeal that envelops everything. Everything is displayed with such youthful energy. Everything is so cultural and compelling. The moment people entered, they forgot that they were in a ghetto. In this exhibition many valuable documents, veritable treasures, are on display: Manuscripts sent from Peretz to Yehoash, letters in Yehoash’s own handwriting. We have rare newspaper clippings. In the section dedicated to Yiddish Bible translations, we have old Yiddish translations dating back to the 17th century. When you look at the exhibit, at our work, you feel truly inspired, and you really do forget that you’re inside a dark ghetto. The celebration, too, went off splendidly…Our kids read compositions about Yehoash’s writings, about Yehoash as the poet of beauty, of music and color. The mood at this celebration was truly exalted. It was a real holiday, a demonstration of Yiddish literature and culture.[5]

The Yehoash exhibition was a unique event in the annals of the Holocaust, a uniqueness that derived in large measure from the Litvak cultural legacy. Although there were only 20,000 Jews left in the ghetto, the Saving Remnant of this once-great community, the exhibition lays bare the values that Avrom Sutzkever was intent upon rescuing. It illustrates what a 15-year-old boy in the Vilna ghetto could learn from Solomon Bloomgarden, also known as Yehoash, who emigrated from Lita to the United States in 1890 at the age of 18, settled in New York City, and died there in 1927.

- Love of the landscape. Yehoash was the first great nature poet in Yiddish; not of his native Lithuanian landscape but of his adopted, American, landscape. He produced a celebrated translation of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha,” which modeled how Yiddish could be used to embrace a world never before encountered. Through Yehoash, Sutzkever demonstrated to his students that the bond between the Jews and their natural surroundings could not be severed. That is because there was no greater nature poet in Yiddish than Sutzkever himself, who just prior to the German invasion had invented a new language to sing the praises of the Lithuanian forests and fields. He called the book Valdiks, Woodlore. Nature, for Sutzkever remained the source of beauty, poetry, artistic inspiration, and creative renewal. Through this exhibition, Sutzkever taught a generation of Jews who were completely cut off from the outside world that nature was the source of “beauty, of music and color,” to quote Rudashevsky.

- Back to the Bible. Yehoash was most famous for his Bible translation, over which he labored many years and that became a modern classic in the poet’s own lifetime. It was a monumental achievement, and as the exhibition demonstrated, was itself a link in the chain of Yiddish Bible translations going back to the invention of printing. What could be more true to the Litvak legacy than the love of Torah, and the zitsfleysh, the stubborn endurance, required to produce a complete translation of the Five Books of Moses, the Prophets and the Writings? Yehoash was the model Litvak because he possessed the mental curriculum required to produce a modern translation of the Hebrew Bible, based on comparative Ancient Near East philology and recent Bible scholarship; a translation that would preserve the diction and syntax of khumesh-taytsh, the oral tradition of teaching Bible in Ashkenaz, yet also be alive to the beauty, music and color of the Yiddish language. Torah scholarship is what Litvaks were famous for and although Yehoash left home at the age of 18, he carried that legacy with him to the New World, where a two-volume Hebrew-Yiddish set of Yehoash became a most valued possession in American-Jewish homes. Thanks to Yehoash, even such radically secular Jews as Yitskhak Rudashevsky were exposed first-hand to the Book of Books.

With the help of our two informants, Masha Roskies and Yitskhok Rudashevsky, we are now ready to diagram the DNA of Jewish collective memory. To the three-pronged construction of Model Person, Model Place and Model Time, we can now superimpose another triad that is more Litvak-specific. This second triad represents new modes and models of Jewish self-understanding that were particularly well-developed in Lita. In Lita, more than anywhere else, the Model Person was turned into the Poet; the Model Place was enlarged to embrace the natural landscape and the Model Time was redefined within a biblical timeframe.

Here’s a simple way to diagram how the two triangles fit together. If you look at it from above, through a timeless perspective, one is overlaid upon another. But if you think of it in historical perspective, imagine these as vectors drawing from one another and away from one another. Lita is where opposites attract, where tradition and modernity coexist. Litvaks thrive on contradiction. They know how to bring things together that have never been brought together before.

That the poet became the model person we know from the examples of Avrom Reisen lamenting the death of A. Vayter and Avrom Sutzkever celebrating the life of Yehoash.

That the love of nature came to reinforce the love of place we know from Yitshak Rudashevsky’s response to the nature poetry of Yehoash and from Suzkever’s invention of his own language of nature.

And that the Bible is the Book of Love we can learn from that great Litvak, the first Hebrew novelist, the first to write a modern love story in a Jewish language–Abraham Mapu.

In 1853, in his novel Ahavat Tsiyon, The Love of Zion, Mapu turned the Bible back into the Book of Love and the Book of Nature, even as he implanted an undying love of Zion in all his youthful readers. From Mapu, Litvak poets learned how best to express their connection to the land. The way to do so was by invoking biblical imagery. To the extent that any place was home, that place was Bible Land.

So here, to illustrate the transformative power of the Bible; to illustrate how the Bible became the most natural Litvak language, is a whirlwind tour of six poets, six of the fifteen poets I listed above. I shall read only a fragment of each poem, in English and in Yiddish. I do so in the hope that you will find something in these poems both familiar and utterly strange. At the very least, they will leave you with an expanded sense of what it means to be a Litvak.

We begin with the poet Leyb Naydus, who was born and died in Grodno. Like A. Vayter, he is remembered as a poet who was cut down in his youth without the opportunity to fulfill his creative potential. Naydus, the most youthful, romantic and decadent of Litvak poets died at the age of 28. His “Intimate Melodies” describe an educated, worldly Jewish male who has fallen under the spell of a wild Gypsy girl named Dzeyma. Today the poem would be considered politically incorrect, because it is unabashedly Orientalist. But in its day, its open eroticism and sophisticated mix of dream and reality, Biblical and European landscapes, caused quite a sensation. Listen for the ancient Near Eastern references: Sidon was a Phoenician port city, from which the wicked queen Jezebel introduced pagan practices into Israel, and take special note of the phrase, “mir dukht zikh, I dream you.” The poem is a biblical fantasy happening in the present. If you have an ear for Yiddish, you will delight in the rhyme of “Tsidn / Sidon” with “midn / weary” and the Hebraic “pilegesh / concubine” with the hyper-European “elegish / elegiac” and enjoy the fact that the poem must be read in Litvish Yiddish in order for it to rhyme.[6]

I love your lustful, fainting-weary gaze,

Dzeyma, and your hair’s coal-black waves;

Your vivid tatters, Sidon’s merchandise

Your dark eye’s desert caves.

So lovely, wildly elegiac, lying

With the long shadow cast beneath your brow;

I dream you: slim and young, a concubine

Brought here from some distant harem now. (286)

Kh’hob lib, Dzeyma, dayn tayve-blik, dem farkhalesht-midn,

Di khvayles fun dayne lokn—shvarts vi keyl [koyl]

Dayne farbike trantes—tayere shtifn fun Tsidn,

Dayn fintseres eyg—a midbershe heyl.

Vi sheyn du bist, ven du ligst azey vild-elegish

Un a langer shotn falt fun dayn brem:

Mir dukht zikh: du bist a yunge, shlanke pilegesh,

Gebrakht ahertsu fun ergets a vaytn harem. (287)

The Bible is brought to life in a completely different way in I. J. Schwartz’s epic poem, Kentucky, which he began writing in 1918, the year he moved there from New York. Other than Yehoash’s translation of “The Song of Hiawatha,” Yiddish readers had never encountered anything like this before. It was the first American Yiddish epic; panoramic, both spatially and temporally. It is the story of a peddler named Josh, who like Joshua before him, has come to conquer the Land of Canaan, in this case, the Land of Dixie, deep in the so-called Bible Belt of the United States. In this segment, we see Josh enjoying his “great secret”: the new home that is being renovated for his family to move into, the most palpable sign that his years of backbreaking labor have paid off. Indeed, Josh’s efforts have been doubly blessed: once by the poet, who lavishes attention on the beauty and bounties of nature, and once by God. Josh, who has long since abandoned Jewish practice, is suddenly reminded in this moment of material success, of Isaac’s prayer to the LORD in Gen. 26:22: “Den oysgebreytert hot undz got / un mir’n zikh farfestikn in land.”

Through the windows of the renovated house,

A green expanse of broad fields and distant woods

And on the pine floor

In a flood of sunlight,

The gold and green swaying shadows

Of the pointed leaves

Of heavy old oaks and young oaks,

It was hard for Josh to tear himself away

From the great secret filling him

Like overwhelming wine;

And looking at the wide expanse,

The old verse would come to mind:

“God hath spread us abroad,

And we shall be established in the land.”

In one important respect, the reimagined Litvak Bible was an improvement over the Hebrew original: Jews and Gentiles now lived in harmony, whether it was Naydus’s young lovers making out in a Gypsy camp, Josh’s children who would soon intermarry, or the fifteen hot-blooded sons in Moyshe Kulbak’s epic poem, “Raysn, Belorussia.” Uncle Avram and the beautiful Nastasya are very much in love, their courtship described in loving detail. It is only in the twelfth and last chapter that Kulbak makes explicit the biblical analogy. This is no mere family of Jewish peasants who drive logs down the Niemen River. It is a veritable tribe of Jews as rooted in the Belorussian landscape as their Biblical ancestors were in the Promised Land. On his deathbed, grandfather blesses his sons, using the very imagery and biblical parallelism that Father Jacob used in Genesis chap. 49. Ortshe the eldest is blessed as if her were Reuben, Rakhmiel as if her were Judah, and Shmulye as if he were Naftali:

You Shmulye, river man; who in the world is like you?

Eternally wet; and always a lash at your shoulders;

Smelling of fish scales, and smells of the scum of the river,

Blessed shall you be on the shore

And blessed on the water. (400)

Du Shmulye, der taykh-mentsh, nito af der velt aza glaykhn!

Bashtendik dem butsh af di pleytses, bashtendik a naser,

Geshmekt hot mit shupn fun dir, mit dem reyakh fun shleym in di taykhn,

Gebentsht zolstu zayn afn land, un gebentsht afn vaser. (399)

For Kulbak, this sense of rootedness, of being completely at home in the rivers and fields of Raysn, came as a natural inheritance. He is the voice of the biblically-inspired family.

Kadia Molodowski was raised in a very different home. Unlike Kulbak, she turned to writing poetry in order to speak to and for her people. What would become, she asked herself in a cycle of poems called “Froyen lider, Women’s Songs,” of those unfortunate Jewish women who grew up dirt poor, were rendered homeless, childless, loveless? The only mothers these women could turn to in their hour of need were their biblical foremothers, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, so familiar to them from the tkhines, or private prayers that Jewish women recited in Yiddish. Here, for example, is the role that Mother Leah can play:

To those who weep at night on lonely beds,

and have no one to bring their grief to,

murmuring to themselves with burnt lips,

to them Mother Leah comes softly,

and covers their eyes with her pale hands. (322)

Tsu di vos veynen in di nekht af eynzame gelegers,

Un hobn nit far vemen brengen zeyer tsar,

Redn zey mit oysgebrente lipn tsu zikh aleyn,

Tsu zey kumt di muter Leye

Halt beyde oygn mit di bleykhe hent farshtelt.[7] (1927)

Litvak poets, female and male, were free to live inside the Bible, to relive the Bible, to make sense of the Bible in terms of contemporary life, and none did so more boldly and memorably than and H. Leivick and Avrom Sutzkever.

No Biblical story captured Leivick’s religious imagination more powerfully than the Akedah, the sacrifice of Isaac on Mount Moriah. The cast of characters was small—a father, a son, a heavenly voice, and a lamb—and the props were very spare—a knife and an altar. Sparer still is Leivick’s language, as epic as the Biblical account itself. But in Leivick’s rereading, the miracle of the Akedah is not Isaac’s last-minute rescue from death but the Akedah itself, “der nes fun nesoyen, the miracle of the test,” the ability of the human being to endure extreme suffering. To be a Jew in Leivick’s scheme is to stand in readiness the next time the knife is at your throat. Each 3-line stanza ends with the same words: “Un—vart., And waits.”

A Voice from above cries, “Stop!”

The hand freezes in air

And waits.

The veined throat suddenly throbs

With the miracle of the test

And waits.

The father gathers up the son.

The altar is bare

And waits.

Ensnared in thorns a lamb

Looks at the hand with a knife

And waits (238)

Derhert zikh fun oybn a bas-kol

—halt op!—blaybt di hant in gliver

Un—vart.