ENGLISH BELOW

Tarp žydų jaunimo autobiografijų, rašytų prieš karą, identifikuotas žymaus Vilniaus istoriografo – Leizerio Rano (1912 – 1995) – dienoraštis, kurį jis rašė būdamas 15-16 metų. Apie dienoraštį, jo identifikavimą ir Leizerį Raną pasakoja Judaikos tyrimų centro darbuotoja Miglė Anušauskaitė.

- Žydų jaunimo autobiografijos ir dienoraščiai

Vilniuje įsikūręs Žydų mokslinių tyrimų institutas (YIVO) 1932, 1934 ir 1939 metais paskelbė konkursus, kuriuose galėjo dalyvauti 16-22 metų jaunimas. Dalyviai buvo prašomi atsiųsti savo autobiografijas arba dienoraščius, kuriuose kuo nuoširdžiau ir atviriau pasakotų apie savo kasdienybę, aplinką, asmeninį gyvenimą ir t.t. Geriausių autobiografijų autoriai gavo piniginius prizus (pirmosios vietos laimėtojas – 150 zlotų), o Žydų mokslinių tyrimų institutas – vertingos medžiagos apie žydų jaunimo gyvenimą.

Daugybė šių autobiografijų, kartu su kitais dokumentais ir knygomis, 1942 m. buvo išgrobstytos nacių ir išvežtos į Vokietiją. Po karo kartu jos buvo perduotos YIVO institutui Niujorke, kur dabar jų saugoma daugiau nei 300. Penkiolika autobiografijų buvo išverstos ir išleistos knygoje „Awakening Lives. Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland before the Holocaust“.[1] Taip pat knygoje „Ostatnie pokolenie. Autobiografie polskiej młodzieży żydowskiej okresu międzywojennego ze zbiorów YIVO Institute for Jewish Research w Nowym Jorku“ (Wyd. Sic!, Warszawa 2003).

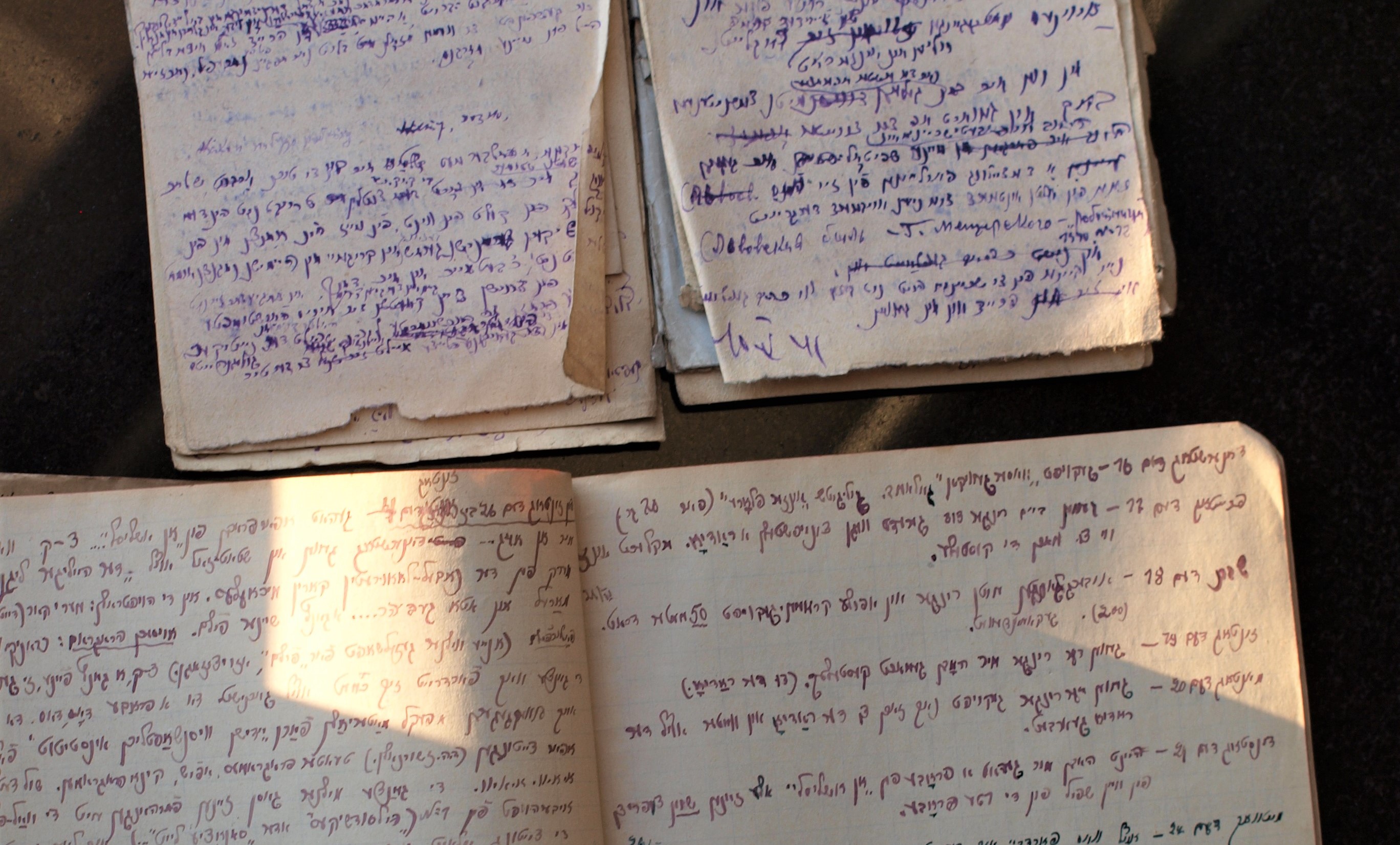

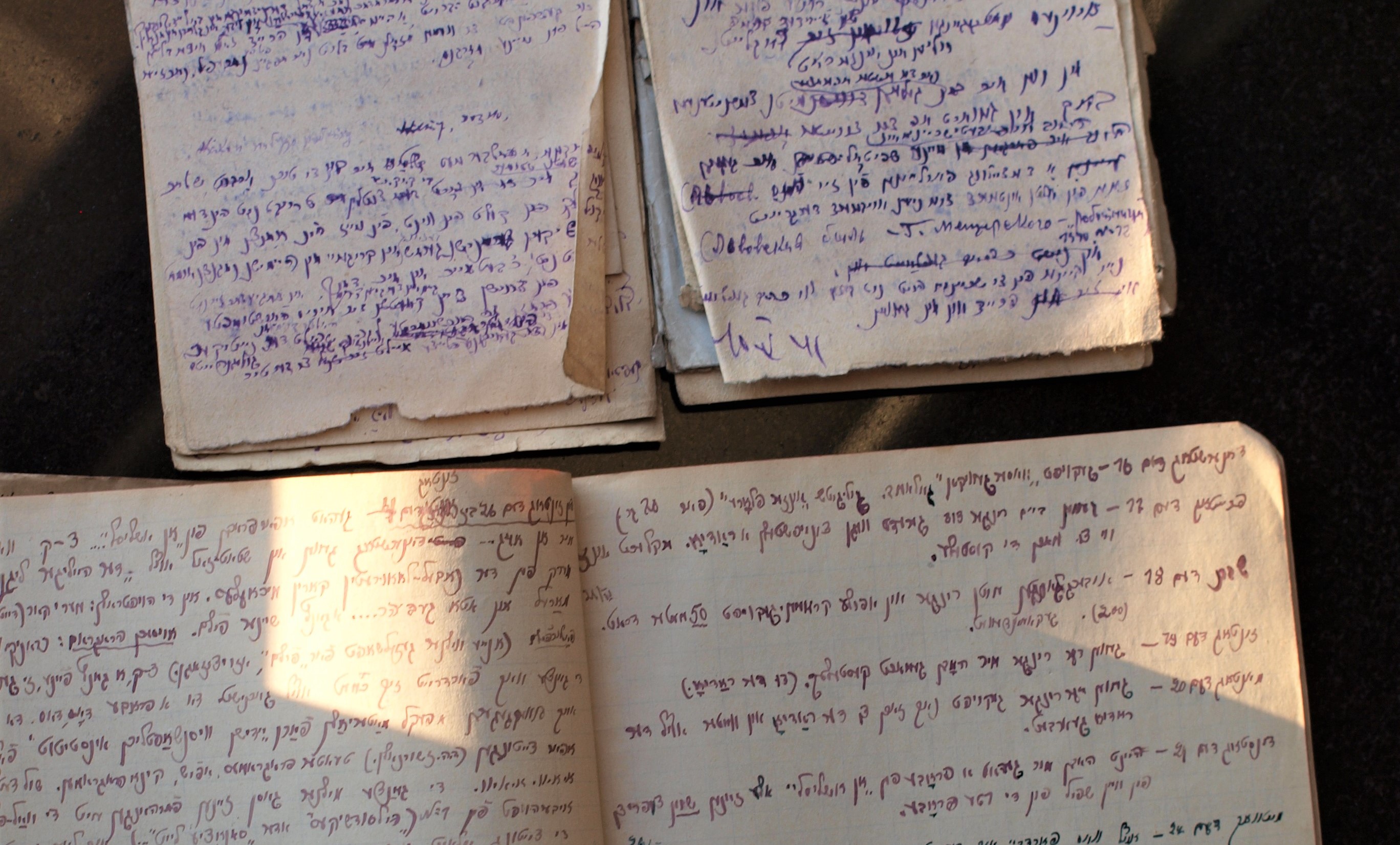

Bet tai – ne visos išlikusios autobiografijos ir dienoraščiai. Neseniai tarp II pasaulinio karo metais paslėptų ir Nacionalinėje bibliotekoje išsaugotų dokumentų rasta dar keliasdešimt YIVO konkursui siųstų autobiografijų ir dienoraščių, iki šiol laikytų pradingusiais.

Su autobiografijomis dirbti pradėjau besiruošdama grafinių novelių autoriaus Ken Krimstein vizitui – jis ieškojo medžiagos savo būsimam kūriniui. Autobiografijas ir dienoraščius rūšiavau, bandydama sudėti į viena to paties autoriaus parašytus išsibarsčiusius sąsiuvinius, identifikuoti autorių vardus ir slapyvardžius, gyvenamąją vietą, lytį ir t.t. Ken Krimstein atsirinko keletą jam įdomių dienoraščių ir autobiografijų, kuriuos vėliau mėginau skaityti ir išversti fragmentus.

Tekstai parašyti daugiausia jidiš kalba, nors yra krūvelė rašytų lenkiškai, keli – hebrajiškai ir vokiškai. Kartais jų autoriai, turbūt gavę vien religinį išsilavinimą hebrajų kalba, jidiš kalbos žodžius rašo iš klausos, taigi nestandartine ortografija, kas apsunkina naudojimąsi žodynu. Nepaisant dėl to kylančių iššūkių, kartais vien iš kelių frazių galima susidaryti įspūdį apie autorės (-iaus) charakterį, išsilavinimą, vertybes, kasdienybę, santykius. Tai neišvengiamai kuria tam tikrą vienalaikiškumo ir artimumo pojūtį. Tačiau vienalaikiškumo jausmą pertraukia prisiminimas apie įvykusį Holokaustą, kurio dauguma autorių, tikėtina, neišgyveno, ir likusios autobiografijos ir dienoraščiai dažnu atveju yra vieninteliai jų gyvenimo ir pasaulėvaizdžio pėdsakai.

Šiame kontekste buvo neįprasta surasti dienoraštį, kurio autorius ne tik išvengė Holokausto, bet ir aktyviai veikė ilgai po jo, į istoriją įėjęs kaip vienas žymiausių Vilniaus metraštininkų.

- Leizerio Rano dienoraštis ir jo identifikavimas

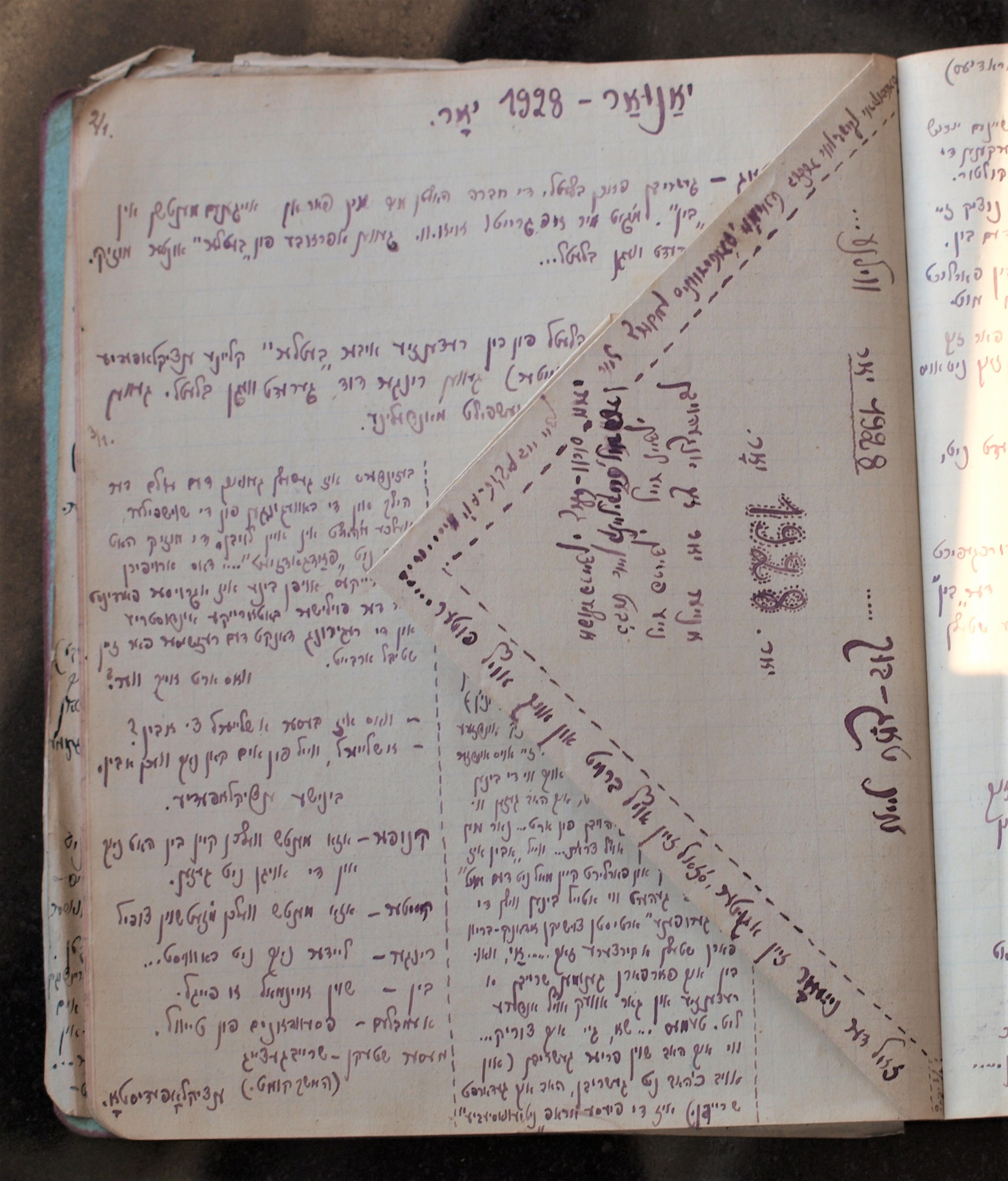

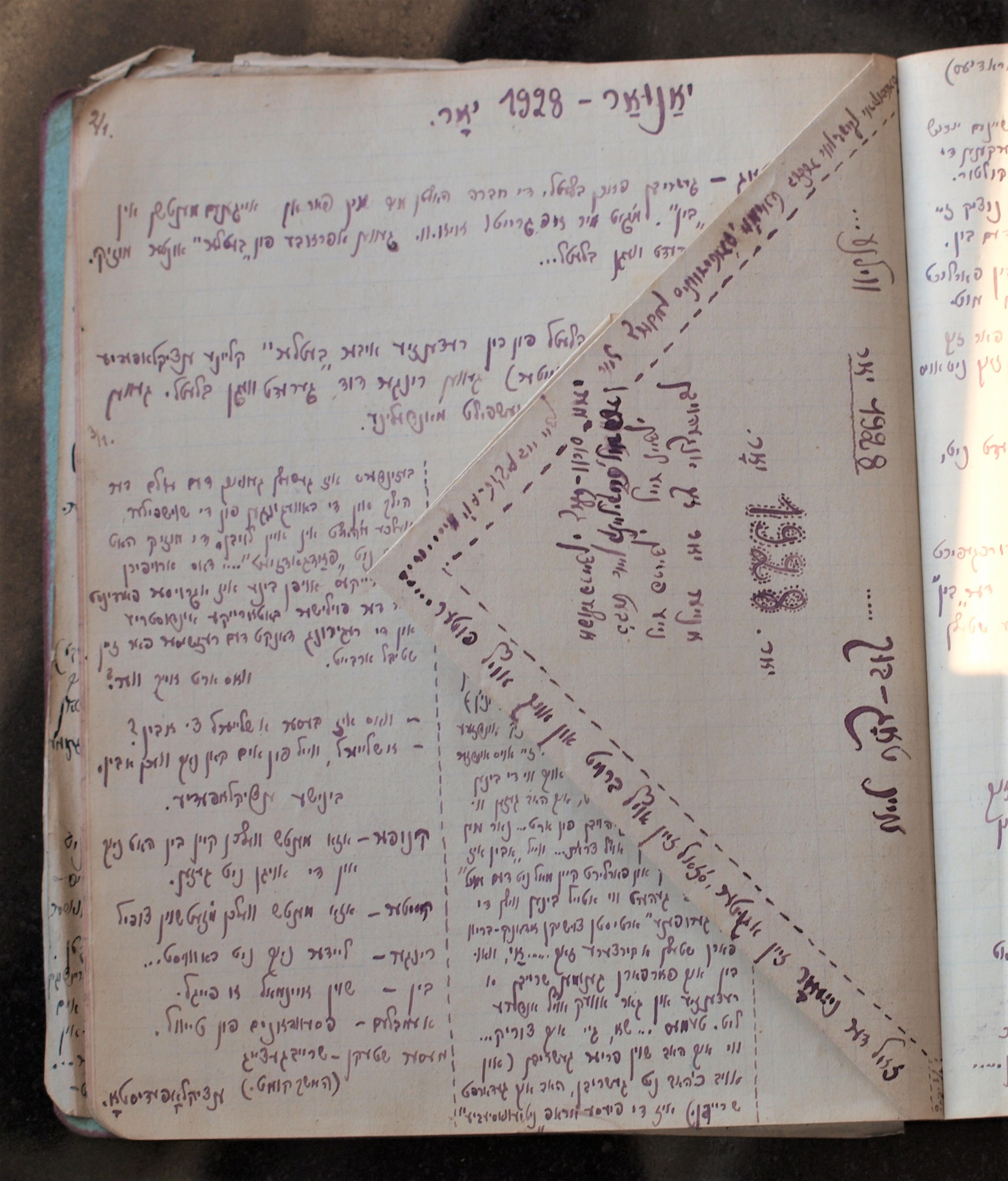

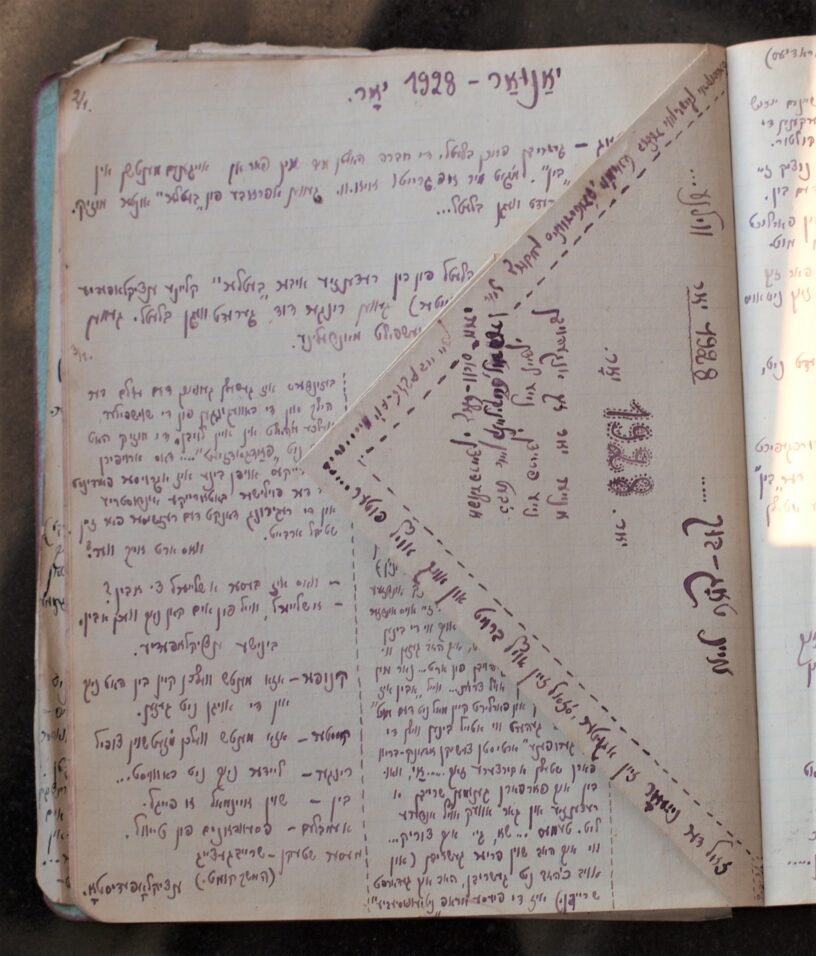

Iš rašto atrodo, kad tai kruopštus, organizuotas žmogus, sugebantis planuoti erdvę: dienoraščio įrašai išdėlioti tvarkingai, vietomis paraštėse tęsiasi skyrelis, pavadintas „Kronika: mano pajamos, išlaidos ir visokios kitokios smulkmenos“. Jis daug pasakoja apie skaitomas knygas, groja mandolina, susitinka su draugais, mokosi kalbų, rašo poeziją.

1927 m. ir 1928 metų įrašus perskiria puošnus puslapis.

Dienoraščio autoriaus tapatybę nustatyti pagelbėjo keli jame cituojami laiškai.

Vienas iš laiškų atkreipė dėmesį, nes buvo pasirašytas vardu „Leizer Ran“ (לייזער ראן). Prisiminiau, kad šis vardas man girdėtas, bet neskubėjau džiaugtis – juk tikėtina, kad dienoraštyje nukopijuotas tekstas, rašytas kažkieno kito.

Kitas cituojamas laiškas pasirašytas grupės žmonių, tarp jų – ir L. Ran (ל. ראן), beje, tarp pasirašiusiųjų yra ir יאוויטש, kuris minimas ir kitur kaip dienoraščio autoriaus bičiulis, su kuriuo šis mokosi lenkų ir esperanto kalbų, žaidžia ping-pongą.

Kiti du cituojami laiškai iš pradžių kėlė daugiau abejonių, nes buvo pasirašyti kitais vardais. Tačiau atidžiau pažiūrėjus ne tik patvirtino autoriaus tapatybę, bet ir atskleidė jo išradingumą. Vienas jų pasirašytas א ווילנער לעזער (A Vilner lezer – „Vilniaus skaitytojas“): viena vertus, tai žaidimas su autoriaus pavarde (Leizer – lezer), kita vertus – svarbi Leizerio Rano veiklos dalis. Žinome, kad Vilniaus „skaitymas“ ir dokumentavimas jam buvo svarbus nuo pat jaunystės: Harvarde saugomoje jo kolekcijoje yra užrašų knygelė su posakiais jidiš kalba, kurioje pažymėta: „1928 m. surinkta Leizerio Rano“.[2] Šis slapyvardis pasirodė ir kone pranašingas, nes Leizeris Ranas ir tapo labiausiai žinomas dėl apie Vilnių surinktos istorinės ir etnografinės medžiagos.

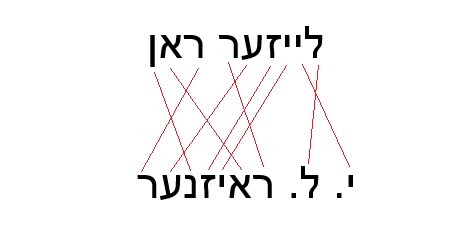

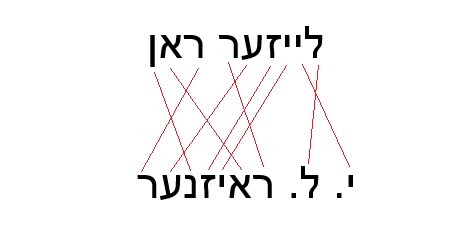

Dar kitas slapyvardis iš pradžių atrodo kaip klaidingai užrašyta pavardė: י. ל. ראיזנער (I. L. Raizner arba Roizner – bet dvibalsiai „ai“ ir „oi“ jidiš kalboje užrašomi kitaip, be א raidės). Tačiau kas savo pavardę rašo klaidingai? Pabandžiau suskaičiuoti raides ir intuicija pasitvirtino: tai – Leizerio Rano vardo anagrama.

Anagramos pasirinkimas – prisiminkime, kad L. Ranui tuo metu tebuvo 15 metų – byloja apie apsiskaičiusį žmogų, mylintį kalbą ir turintį humoro jausmą. Tokios charakteristikos atsispindi L. Rano dukters Faye Ran rašytame straipsnyje apie tėvą: „Nors mano tėvas buvo nepaprastai gabus lingvistas ir literatas, jis buvo kuklus žmogus, turintis patrauklų humoro jausmą ir įkvepiančiai sąžiningas.“[3]

Palyginus rankraštį su kitais, jau identifikuotais, Leizerio Rano ranka rašytais dokumentais, autoriaus tapatybė galutinai pasitvirtino.

Į dienoraščio pabaigą įrašai darosi mažiau tvarkingi, dingsta „kronikos“ skyrelis. Maždaug ketvirtadalis sąsiuvinio lapų – paskutinioji dienoraščio dalis – iškirpta: iš likusių atplaišų matyti, kad ji irgi buvo užpildyta tekstu. Galbūt autorius pats jas iškirpo, prieš teikdamas dienoraštį YIVO organizuotam konkursui, o gal galime tikėtis, kad trūkstami lapai dar atsiras, rūšiuojant atrastuosius dokumentus.

Paskutiniajame iš išlikusiųjų puslapių cituojamas posakis:

„Kai esi pavojuje – dainuok,

Kai tau skauda širdį – juokis.“

Dienoraščio atradimas – tai galimybė pažvelgti į Vilniaus dokumentuotojo paauglystės metus. Po to sekusi Leizerio Rano gyvenimo istorija žinoma geriau: yra jo paties memuarų, draugų ir artimųjų atsiminimų ir, žinoma, jo didįjį darbą – dokumentų apie Vilnių kolekciją.

- Leizerio Rano gyvenimas ir darbai

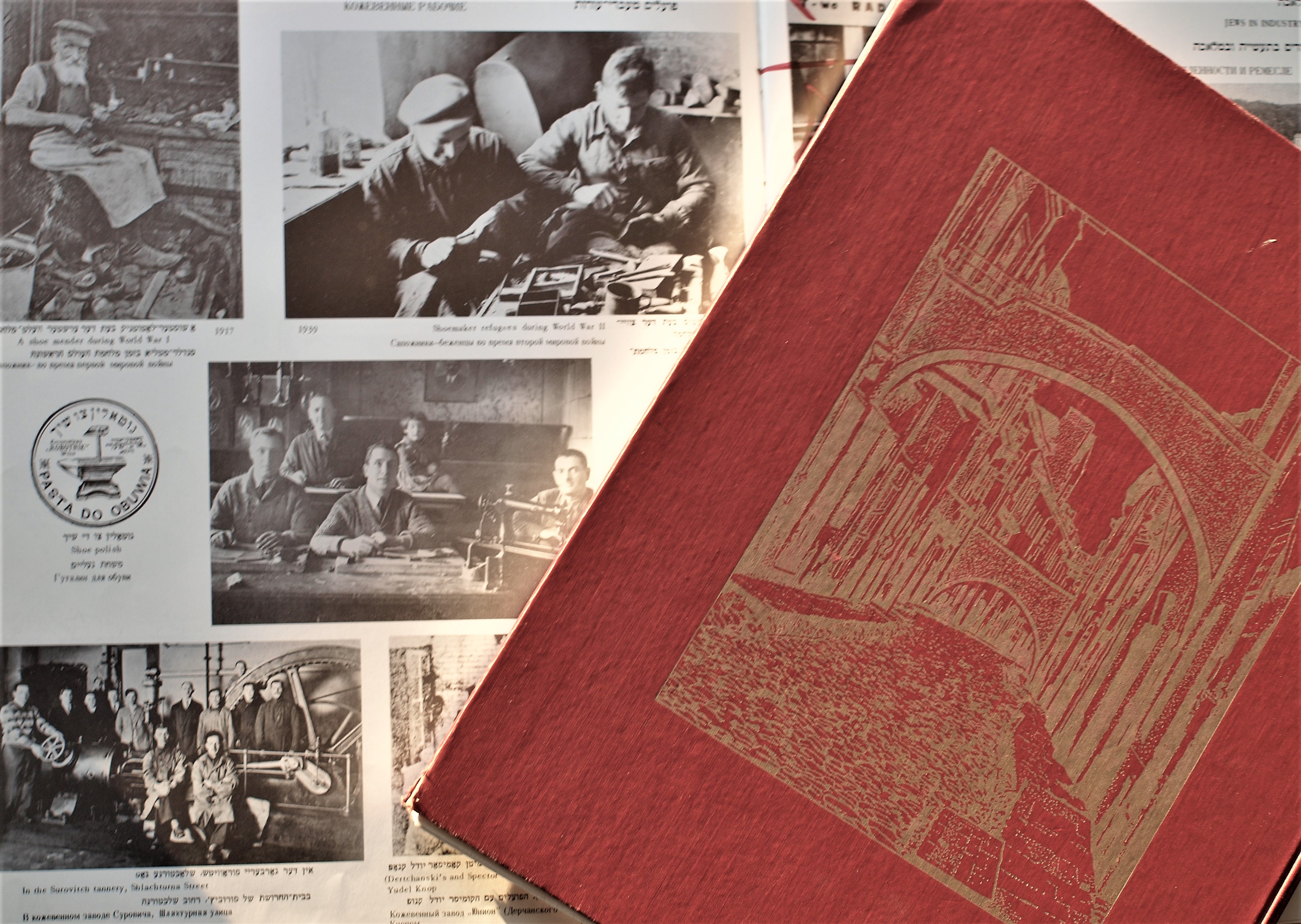

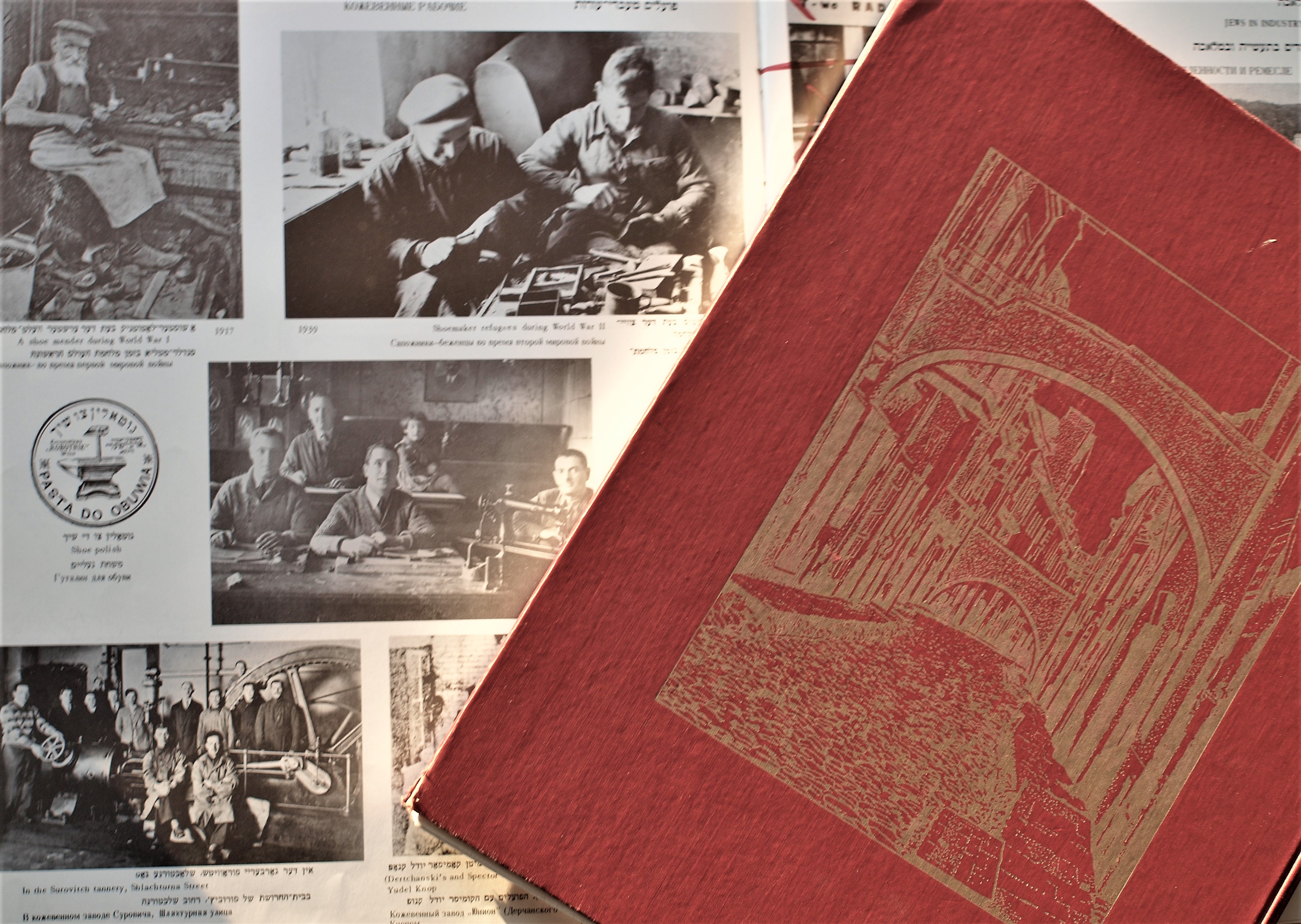

Didysis LeizerioRano darbas – 1974 m. išleistas trijų tomų albumas „Yerusholaym d‘Lite: The Jerusalem of Lithuania“.

Jau pirmoje XIX amžiaus pusėje Vilniaus žydų bendruomenėje atsirado norinčių įamžinti savo miestą ir bendruomenę, išsaugoti jos atminimą.[4] Nuo kitų prieš II pasaulinį karą Vilnių dokumentavusių istoriografų Leizeris Ranas skyrėsi tuo, kad domėjosi ne vien iškiliais asmenimis – jis siekė rekonstruoti visą miesto daugialypumą, taigi ir paprastus žmones, išmaldos prašytojus ir vandens nešiotojus, mokytojus ir pirklius, batsiuvius ir rabinus, pribuvėjas ir motinas, teatrą ir muziką…[5]

Dokumentuoti Vilniaus gyvenimą Leizeris Ranas pradėjo dar prieš karą: jis dirbo Vilniuje įkurtame Žydų mokslinių tyrimų institute (YIVO), tuomet gavo stipendiją Maskvoje ir išvyko ten kaip tik prieš karą, šitaip išvengdamas Holokausto. Tačiau Maskvoje Leizeriui Ranui ir jo žmonai Baševai Ran irgi nebuvo saugu – jie buvo suimti per masinius areštus, melagingai apkaltinti šnipinėjimu ir ištremti į Samarkandą, iš kurio jiems vėliau padėjo pabėgti tenykščio žydų pogrindžio atstovai. Grįžę į Vilnių sutuoktiniai atrado mylimo miesto griuvėsius.[6] Išvykęs į Paryžių, tada gyvenęs Kuboje ir galiausiai – Niujorke, Leizeris Ranas nenustojo rinkti dokumentų apie kadaise klestėjusią Vilniaus žydų bendruomenę.

Harvarde saugoma didžiulė jo surinktų dokumentų kolekcija neseniai padaryta prieinama plačiajai visuomenei.

[1] Shandler, Jeffrey (ed.), Awakening Lives. Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland before the Holocaust, (New Haven: Yale University Press in cooperation with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2002).

[2] Zalkin, Mordechai (Motti). „Return to „Jerusalem of Lithuania“: A Stroll through the Leyzer Ran Collection Archive“. In Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. By Berlin, Charles. P. 17.

[3] Ran, Faye. „Leyzer Ran (1912-1995): Linguistic and Literary Prodigy, and Champion of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit“, in Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. By Berlin, Charles. P. 3.

[4] Zalkin, Mordechai (Motti). „Return to „Jerusalem of Lithuania“: A Stroll through the Leyzer Ran Collection Archive“. In Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. ByBerlin, Charles. P. 17.

[5] Ten pat, p. 18.

[6] Ran, Faye. „Leyzer Ran (1912-1995): Linguistic and Literary Prodigy, and Champion of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit“, in Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. ByBerlin, Charles. P. 3-5.

A diary of the famous historiographer of Vilnius – Leyzer Ran (1912 – 1995) – that was written during his teenage years (15-16), was identified among the autobiographies of Jewish youth. A researcher of Judaica Research Center Miglė Anušauskaitė tells about the diary, its identification and life of Leyzer Ran.

- Autobiografies and diaries of Jewish youth

Vilnius-based YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in 1932, 1934 and 1939 announced contests aimed at Jewish youth of 16-22 years. The participants were asked to send in their diaries or autobiographies, containing honest accounts on their everyday life, surroundings, personal life etc. The authors of best autobiographies received prizes of 150 zloty, and the Institute for Jewish Research got invaluable material about the life of Jewish youth.

Many of these diaries and autobiographies, together with other books and documents, were pludered by nazis in 1942 and brought to Germany. After the war they were given to YIVO institute in New York, about 300 of them currently in YIVO’s possession. 15 of them were translated and published in a book „Awakening Lives. Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland before the Holocaust“.[1] Some more were published in a book “Ostatnie pokolenie. Autobiografie polskiej młodzieży żydowskiej okresu międzywojennego ze zbiorów YIVO Institute for Jewish Research w Nowym Jorku” (Warszawa 2003).

But these are not only surviving autobiographies and diaries. Recently among the documents that were hidden during the war and preserved in the National Library of Lithuania, a few dozen additional diaries and autobiographies were found, thought to have dissapeared until now.

I have started working with these autobiographies while preparing for the visit of graphic artist Ken Krimstein, who was searching for material for his next work. He has chosen some of the autobiographies and diaries, which I then started reading and translating fragments for K. Krimstein.

Most of them are written in Yiddish, in addition to a small pile in Polish, and a couple in Hebrew and German. Some authors most likely had only religious education in Hebrew, and thus tey write Yiddish as they hear it, not according to standard orthography, which makes it harder to use a dictionary to translate. Despite the challenges, sometimes a few lines of text is enough to get the feeling of author’s character, education and values. While working with them it’s impossible not to feel a certain proximity and simultaneity, but that feeling is interrupted by the remembrance of Holocaust, which many authors possibly didn’t survive. In this case their autobiographies and diaries are possibly the only traces of their lives and worldviews.

In this context it is unusual to come upon a diary the aothor of which not only escaped the Holocaust, but was active many years after that and became famous as one of the most distinguished chroniclers of Vilnius.

- Leyzer Ran’s diary and its identification

The handwriting gives an inpression of a thorough, organized person: diary entries are tidy, sometimes in the margins a section of a “Cronicle” appears, under which the author documents his “income, expense and other various small things”. He’s documenting the books he reads, he plays mandoline, meets friends, is learning languages, writes poetry.

The entries of 1927 and 1928 years are separated by a decorative page.

A couple of letters quoted in a diary helped to identify author’s identity.

My attention was drawn to one of the letters, signed “Leyzer Ran” (לייזער ראן). I remembered hearing this name elsewhere, but I tried not to get too excited at first: it is still possible he was quoting a letter written by somebody else.

Another letter was signed by a group of people, the name of L. Ran (ל. ראן) among them. Another name (יאוויטש) appears there too, the same person mentioned elsewhere in the diary as the author’s friend, with whom he’s learning Polish and Esperanto and playing ping-pong.

Two other letters, quoted in the diary, caused more doubts, because they were signed in different names. But after looking at them more closely, they didn’t only confirm the identity of the author, but also revealed his ingenuity. One of the letters was signed א ווילנער לעזער (A Vilner lezer – The Reader of Vilna): on one hand, it’s a wordplay with the name of the author (Leyzer – lezer), on the other hand, it represents an important part of Leyzer Ran’s activity. We know he was interested in ‘reading’ and documenting Vilna city right from the young age. Evidence of his early historiographic awareness appears on the inner binding of an old notebook found in this collection and containing hundreds of expressions in Yiddish: „collected by Leyzer Ran, Vilna, 1928.“.[2] This pseudonym proved to be prophetous, as Leyzer Ran became known exactly because of the historiographic and ethnographic material about Vilnius.

Another pseudonym at first ressembles an incorrectly written name: י. ל. ראיזנער (I. L. Rayzner or Royzner: but the diphtongs “ay” and “oy” in Yiddish are written without א). But who writes his own name incorrectly? I tried counting the letters and the initial intuition proved to be correct – it’s an anagram of Leyzer Ran’s name.

The choice to write his name as an anagram – let’s recall that Leyzer Ran was only 15 at the time – reveals a well-read person, humorous and with a good sense of language. These characteristics reflect in Faye Ran’s (the daughter of Leyzer Ran) article about her father, where she describes him as prodiguous linguist, but at the same time a humble man, with an engaging sense of humor and inspirational honesty.[3]

Having compared the handwritting in a diary with other, already identified, examples of Leyzer Ran’s handwriting, the identity of the author seems to be positive.

At the end of the surviving diary, its entries become more chaotic, the “cronicle” disappears. The last quarter of pages are cut out: from the remaining parts we can see that they were also filled with text. Maybe the author had cut them out himself, before submitting the diary to YIVO contest? Or maybe we can hope to find the remaining parts among other documents in the National Library.

In the last remaining page Leyzer Ran quotes a saying:

“When you are in danger – sing,

When you have a heartache – laugh.”

Discovery of this diary is a possibility to glance at the teenage years of the chronicler of Vilna. Later parts of his life story are better known from his own memoirs and those close to him, and, of course, from his master work – the collection of documents on Vilna.

- Leyzer Ran’s life and works

Leyzer Ran’s masterwork – 3 volumes of the album „Yerusholaym d‘Lite: The Jerusalem of Lithuania“, published in 1974.

At the first half of XX century in the the Jewish community of Vilna there were already attempts to document the city and its Jewish community, to preserve its memory.[4] Unlike other historiographers of the time, Leyzer Ran was interested not only in prominent personnas, instead, he wanted a „complete, multi-faceted recontsruction of the city and its fullness“, including common people, „beggars and water-carriers, „Melamdim (teachers) and merchants, cobblers and rabbis, midwives and mothers, theater and music…“[5]

Leyzer Ran started documenting Vilna even before the war: he studied and worked in YIVO, which was founded in 1925. Before the II world war broke out, he moved to Moscow, where he had received a fellowship. There he and his wife Basheva Ran became victims of mass arrests, falsely accused of espionage and sent to exile in Samarkand. They escaped from Samarkand with help of the local Jewish underground. They returned to Vilna and found the beloved city in ruins. After that Leyzer and Basheva Ran moved to Paris, later lived in Cuba and in New York.[6] During all this Leyzer Ran never stopped gathering documents about Jewish Vilnius.

[1] Shandler, Jeffrey (ed.), Awakening Lives. Autobiographies of Jewish Youth in Poland before the Holocaust, (New Haven: Yale University Press in cooperation with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2002).

[2] Zalkin, Mordechai (Motti). „Return to „Jerusalem of Lithuania“: A Stroll through the Leyzer Ran Collection Archive“. In Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. By Berlin, Charles. P. 17.

[3] Ran, Faye. „LeyzerRan (1912-1995): Linguistic and Literary Prodigy, and Champion of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit“, in Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. By Berlin, Charles. P. 3.

[4] Zalkin, Mordechai (Motti). „Return to „Jerusalem of Lithuania“: A Stroll through the Leyzer Ran Collection Archive“. In Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. By Berlin, Charles. P. 17.

[5] Ibid, p. 18.

[6] Ran, Faye. „Leyzer Ran (1912-1995): Linguistic and Literary Prodigy, and Champion of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit“, in Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library. Cambridge, 2017. Ed. ByBerlin, Charles. P. 3-5.

Parašykite komentarą